Selected Reviews

Andrew Young at David Beitzel

Artforum, January 1993

- Justin Spring

|

David Beitzel Gallery, New York

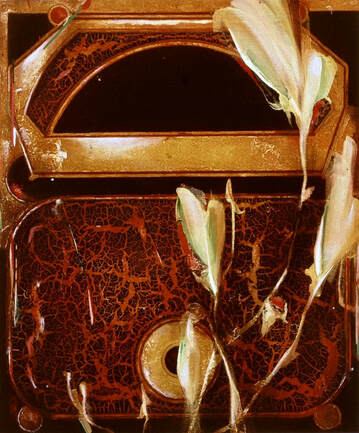

At first they seemed simply handsome and restrained, but over time, Andrew Young’s paintings do act on the mind gradually and indirectly. They reveal themselves to be much less stable, much more complicated and disturbing, than they at first appear. Almost aggressively elegant, calm, and self-possessed, each work keeps rather determinedly to itself, exerting an atmospheric influence. A viewer is tempted not to get too involved since the paintings seem so preoccupied with one another, so much of a piece. And besides, the particular representational conceits of the paintings―their windowsills, orchids, and decorative stencils―are a little claustrophobic. The work seems to lack air. The colors―champagne and navy; mauve, brown, and cream―are similarly closed: they convey a sense of luxury and high style, but seem uncomfortably self-satisfied. Spend a little time with them up close, and that first impression quickly fades. What you thought you saw in those paintings--the stiff self-absorption of so many dried-flower arrangements--now disintegrates into shapes and forms and images of less determinate origin: just splotches and brushstrokes really, sinking, dreamlike, under all those layers of egg-tempera glaze. The flatness of the first images dissolves into energetic splatters and dried, cracked patches: a paint surface so fascinating that what previously seemed a unified whole now seems about to fall apart entirely, all that stillness broken up into a crackling maze of near-biological complexity. This surface, far from slick, is almost frightening: like something left too long in the back of a refrigerator. Or, if you will, some state of consciousness, in which, for just a moment, the ultra-rational mind relinquishes control and strange things bubble up: a shadowy place where emotion, triggered by the senses, is reinforced by memories of what may or may not have been, but is nonetheless crucially important. |

Understood by Weather, 1992.

Egg tempera on wood panel, 46 x 32.5 in. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX |

|

What She Leaves Us, 1992

Egg tempera on wood panel, 23.5 x 20 in. |

Which leads me to think that these are not simply paintings of flowers or spheres or stencils, any more than they are paintings of color, texture, and space. And while one could argue that they represent some intellectual idea about contemporary painting, the paintings themselves seem to describe something else: a visceral and emotional state that is really only half identifiable yet far more real, and far more compelling, than mere good looks or clever remarks. Something as much about the past, present, and future, as much about the interaction of the conscious with the unconscious, as, say, falling in love.

Marcel Proust finds this world of twilight consciousness, of peripheral recognition and intense emotional awareness, in the workings of memory, locating with excruciating precision the moment when physical sensation triggers recollection. He captures these moments by beginning with a sensory event that evokes the past - the scent of May blossoms, a phrase from a sonata, the taste of a madeleine soaked in tea - then developing the path that memory takes in richly textured prose. Both are, in the end, equally important to our understanding of his state of mind. Andrew Young presents similar moody images to us, with an equally elegant precision and complicated vocabulary, in these beautiful, well-crafted paintings. |