Selected Reviews

Grains of the Real: Andrew’s Egg Tempera

Dawn Review, January 18, 1994

- Dr. Akbar Naqvi

|

In the anxiety to present Andrew Young as an egg tempera artist, we are likely to miss the point that he is primarily a painter who uses this medium by choice. Obviously, it gives him qualitative advantages, in what Shakespeare called “bodying forth,” his perceptions and thoughts which painting in oil may not enable him to do. Andrew Wyeth, a great painter of this medium, spoke at some length to Thomas Hoving years ago and described egg tempera in terms of the earth and earth colours. He sounded as if nothing else would have allowed him to physically hold his “subject” in his hand. To him, tempera felt like the mud of his beloved land, and if you were to ask our own Riffat Alvi about her use of pigments made from the soil, she would add that mud to her is colour aplenty as rich as the rainbow.

Oil painting is essentially a medium of transubstantiation; tempera, on the contrary is the gift of resurrecting bodies from the dead. Going as far back as the Hellenist Greek art, this medium favored realism and humanism of a kind which was both pristinely visual and warmly palpable. Painters believed that they were painting what was real, not its image. |

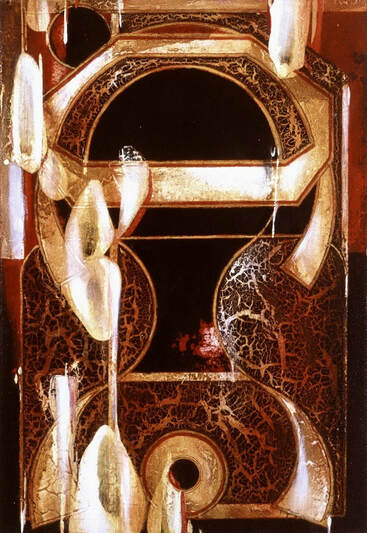

Lines in Relief, 1993

Egg tempera on wood panel, 23.5 x 16.5 in. |

Tempera painting is a text on phenomenology as Merleau Ponty would have us understand the concept when applied to art. For example, Ponty says that the colour of a carpet is “the carpet made of wool… and has certain weight and resistance to sound.” According to him, phenomenology involves the description of things as one experiences them, or, of one’s experience of things,” and he qualifies this statement by adding that “one important class of such experience of things is perception―seeing, hearing, touching and so on.”

It is incredible that Wyeth should tell Hoving his impression of people, objects on land in a similar language. When Giotto painted his Christian heroes, he wanted people to see the real persons and not their images. Picture-making, and illusionism came much later with the invention of oil painting in the Netherlands in the 15th century, and with the camera in France in the 19th century.

It is incredible that Wyeth should tell Hoving his impression of people, objects on land in a similar language. When Giotto painted his Christian heroes, he wanted people to see the real persons and not their images. Picture-making, and illusionism came much later with the invention of oil painting in the Netherlands in the 15th century, and with the camera in France in the 19th century.

|

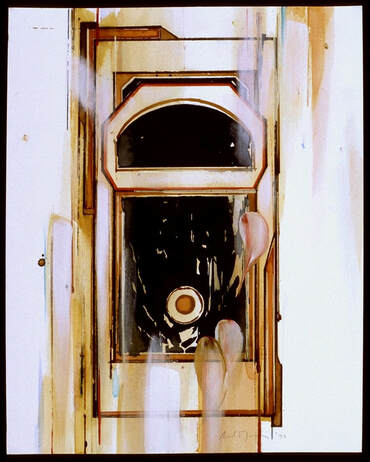

Untitled (wc-87), 1993

Watercolor and gouache on museum board, 20 x 16 in.. |

Tempera is a difficult medium to handle. It requires hard work and patience. Painters have to be painstakingly disciplined to a linear vision which Wyeth calls “techniques.” Because the medium gives its best when its discipline is respected, painters have to pre-plan their strategy of freedom in terms of poetry of faith or the mystique of paganism. The Italians called the discipline “designo”, or design which was principally a matter of drawing, what Wyeth calls the use of pencil. Story telling and characterization in situations have been its forte, traditionally, in the service of the Church or Renaissance Humanism. After the subject was drawn and painted with corrections allowed by the medium what remained on the wall was not just colours but the grains, mass and weight of the pigment not matter how infinitely small they were. Siennese painters were more colorful than the Florentines in terms of hue and brilliance because they continued to see much merit in what was being jettisoned fast under the rubric of “Gothic” barbarities and incompetence in the arts. |

The spirit and even character of bible illumination and the brilliance of colouring in miniatures of the Middle Ages were preserved in Sienna with new changes introduced by the renaissance. In the press releases from galleries, which pass off as critical notices, much has been made of Andrew Young’s Siennese colours. This is misleading, because his is not a Seinnese incarnation. One thinks of the laps lazuli blue of Pietro Lorenzetti’s Crucifixion, the colours of Simone Martini, each colour an independent entity as an object. One also recalls Fra Angelico’s Presentation in the Temple and is overwhelmed by the pageant and heraldry of his colours, each solid and symbolic at the same time… Andrew Young does things with his colours which would be described as contemporary, of our own world of confusion, uncertainties and ambiguities.

|

His colours are hard, like thin metallic skins on his panels. They melt, however, into softness, as of yielding love, in his delectable water colours. Compare the two media to see the differences between discipline and freedom, to appreciate tension between technique and expression in one and the ineffability of tones with their geometric governance in the other. The architectonics of tempera, built layer upon layer, glazes upon glazes, gives it the tactile qualities of a wall surface, and Andrew Young weighs the value of the grains of his pigment like a goldsmith. After all, it is not for nothing that this medium had goldsmiths working for it, and Rosa Maria Letts, in her short book The Renaissance, call Verrochio and Botticelli among others, great goldsmiths.

His key holes, round discs, which in Hindu mythology gods use with effect to whirl off for slaying demons, vines and flowers have the metallic hardness and edged sharpness. Organic and supple they are not and appear to be transfixed in the sharp pictorial gaze of the panel. The effect of cracking paint, which appears like delicate lacy lines add to the decoration of the panel; they look youthfully fresh even when intended to remind us of age. |

Untitled (wc-89), 1993

Watercolor and gouache on museum board, 20 x 16 in. |

The key hole image, open and inviting, resonates with meanings. This image could be interpreted in various ways, as a serious sexual innuendo, or, a teasing picture. Perhaps beyond the key hole, which could open into a closet, there is a tenebrous darkness of, perhaps, Professor Hawking's dark crumbling holes. The hole is not black, but built with glazes into a pit in which colours collapse and die. It is good that the painter leaves us on the horns of, what I would call, ambiguity. What is apparent is that the painter does not have a straightforward story, but a possible secret too deep for paint even. Since he has thrown the key to the lock away, we must allow him his defiance.

There have been great twentieth century tempera painters in the United States. Differences of personalities and impulses apart, what is common to all three is their prediction for what Husseri called “return to things themselves,” a kind of hard and sharp realism very different from the camera’s arrest of reality, something in the nature of coexistence with man and his land at “their maximum articulation.”

There have been great twentieth century tempera painters in the United States. Differences of personalities and impulses apart, what is common to all three is their prediction for what Husseri called “return to things themselves,” a kind of hard and sharp realism very different from the camera’s arrest of reality, something in the nature of coexistence with man and his land at “their maximum articulation.”

|

Toys Already, 1992

Egg tempera on wood panel, 27 x 17.5 in. |

Wyeth touches his people and land when they are fully dressed; Jarred French and Paul Cadmus, two other great tempera painters contact bodies, dressed or otherwise. Look at Wyeth’s Indian Nogeeshik, who is his own self, body and soul, and who signifies Wyeth’s humanism; see French’s The Crew and Cadmus’s Hellenistic The Haircut in which dress is the sensuous skin of the bodies.

You will find that tempera is capable of a wide range of touch and feel. It lends itself to affirmative presences. I feel that the medium is for figurative painting, for story-telling, a kind of new comic book which would put Lichtenstein to shame. Cut-off decoration by itself does not do it full justification. Nor does it help when in search of free expression, the panel is deliberately blemished with touches of abstract expressionism. Perhaps, the best way to see Andrew Young’s paintings is to treat them as fragments from larger wall paintings, say a piece of decorative design from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Effects of Good Government or a still life or decorative detail from a Pompeiian villa fresco. We are used to fragments in museums with or without walls. Thus isolated in time they would reveal their charm, decorative and secretive, and show off their own colours to the best advantage, that is as bodies tanned by the afternoon sun. |

Let me conclude with Merleu Ponty saying that, “Colour in living perception is a way into the thing,” and Wyeth claiming that egg tempera is “incredibly lasting” like the Egyptian mummy, a marvelous beehive or a hornet’s nest.” We seem to be back to traditional values of visual clarity, feeling for reality and poetry of meaning. After the impermanence of so much of what is called art in the States, and is there as pictures in the catacombs of museums, objects need to be given their character and perceptive invitation. Art is endeavour after the real, and in an age in which it has been vulgarized as image, means must be found to keep the search on. Andrew Young’s pictorialism is a reaction against photography and photographic images. Perhaps, this is the only honourable course left to painting.