Selected Projects

Sounds of the Southern Ocean

Antarctic Expedition: NOAA and Oregon State University, 2006

Dr. Robert Dziak, Project Leader

|

In the curator’s preface for the Koehnline Museum of Art’s “Harbour” exhibition catalog, Nathan Harpaz reflected on my experience with public art controversies in graduate school and the process which followed:

“Young reacted to these troubling episodes not by creating political images, but by expressing a sincere concern about society’s abdication of responsibility toward the natural world. He believes that human beings are rapidly losing their sense of connectedness to the earth and to one another, with destructive consequences.” |

With a crew of 40, the Russian Yuzhmorgeologiya was also a supply ship, commissioned to replenish the Korean base with food and other necessities for the year.

|

|

The research vessel, docked at Punta Arenas, Chile, with part of the American team. Left to right: Bill Hanshumaker, Joe Haxel, Bob Dziak, and Haru Matsumoto.

|

With professional experience as a biologist and a continued fascination with nature expressed through art, the issue of human proximity to our surroundings has always been a theme in my work. As much in a physical way – the growth and movement of populations, the limits of natural resources – as in a romantic or, one might say, spiritual one, Nature has been both an abstraction and an inspiration.

|

|

In November, 2006, Dr. Robert Dziak of the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport, Oregon, invited me to participate in an expedition to the Bransfield Strait along the Antarctic Peninsula. As director of the Center's acoustic monitoring project, Dr. Dziak has the support of NOAA's (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Ocean Exploration Program to collaborate with scientists from Korea detecting previously unknown seafloor volcanic and marine mammal activity, as well as ice movement, in the region. Using sophisticated deepwater "hydrophones," the team collects and inspects data from previously deployed instruments - set the year before in the 6000-foot depths - and prepares them for another twelve to fourteen months of work on the ocean floor.

|

Andrew Young surveying a pod of Fin Whales as the ship traversed the Drake Passage toward Antarctica. They are filter-feeders, and considered the second largest whale in existence, measuring up to 80 feet in length.

|

|

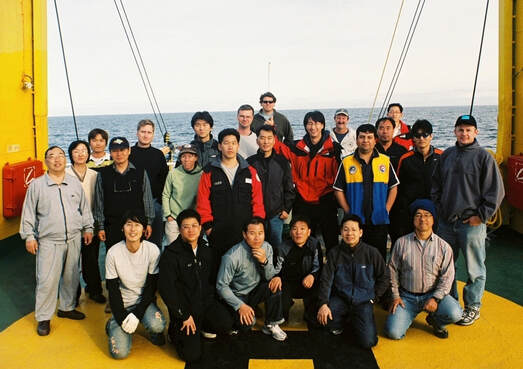

Dr. Dziak’s research was a collaboration with a team from Korea,

seen here also with over-wintering scientists on their way to their King George Island base. |

Dr. Dziak uses techniques unique in the field, employing a thermocline in water temperature as a natural conduit for the subtlest vibrations and triangulating the information for the exact location of their sources. Everything from earthquakes to whale pods, to ice-calving, “scraping” and collisions can be detected and deciphered, rendering, in a way, through sound, a picture of an otherwise invisible world. |

|

Performing a deep-ocean sediment “grab” sample. Ancient sediments can tell us much about the Earth and its climate many thousands of years ago.

|

The Black-browed Albatross is a medium-sized albatross, with an 80 to 95- inch wingspan. It can have a natural lifespan of over 70 years. Many of these followed our ship for miles, seeming to only glide and rarely beat their wings.

|

|

Haru Matsumoto “communicating,” via underwater speaker, with the instruments placed the previous year. Data-gathering elements are anchored to the sea floor by acoustically sensitive release mechanisms, and strung vertically by 500-lb foam buoys.

|

Retrieving the buoy (and instruments) after it was released from it’s anchor and location. It expands several-fold as it rises to the surface from thousands of feet below.

|

|

Below is Dr. Dziak's summary of the project:

The Southern Ocean surrounds Antarctica and serves as a conduit between the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. Yet because of severe climatic conditions, much of this ocean basin remains unexplored. The polar regions play key roles in the global environment and one goal of our project is to document linkages between changes to the Antarctic ice sheet and the volcano-tectonic seafloor processes in the region. To meet the challenge for continuous monitoring in this extreme environment, during December 2005 we deployed an array of Autonomous Underwater Hydrophones (AUH). |

Sunset on Deception Island – an active volcanic caldera – as we sailed into the Bransfield Strait of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was midnight, our first view of what is sometimes called “The Ice,” and also my 44th birthday.

|

|

First claimed by Britain in 1819 and named after King George III, the island is the largest of the South Shetland Islands and home to numerous international research stations. Human habitation of King George Island is limited to bases belonging to Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, South Korea, Peru, Poland, Russia and Uruguay. Most are permanently staffed, conducting research in areas such as biology, ecology, geology and paleontology. Over 90% of the island’s surface is permanently glaciated, but this is declining now at a rapid, unprecedented rate.

|

This new ocean-sensor technology uses cold-water capable, deep-ocean hydrophones to provide the first-ever comprehensive record from Antarctica of the sounds generated by moving ice sheets, undersea earthquakes and volcanoes; even vocalizations from large baleen whales. We recovered and redeployed the AUH array in 2006 and our initial data review indicates the hydrophones recorded hundreds of earthquakes from the seafloor spreading centers and submarine volcanoes within the Bransfield Strait, as well as events from the subduction zone off the South Shetland Islands and from throughout the Scotia Sea. Moreover, we have observed harmonic tremor produced by the movement of large icebergs, and have detected the vocalizations of several critically endangered cetacean species.

|

|

These nesting Gentoo Penguins are most closely associated with Adélie and Chinstrap Penguins, all three adapted to very harsh cold climates. November in the Southern Hemisphere is the spring season, and Gentoo Penguins make nests from a roughly circular pile of jealously guarded stones. Laying two eggs, the parents share incubation (changing their duty daily), and the chicks hatch after about 35 days.

|

The method for going ashore from the ship is to don insulated “survival suits,” climb down a thirty-foot rope ladder, and ride an inflatable Zodiac boat around floating ice to the base’s dock.

|

|

Some non-seafaring days were spent with the Korean Ocean and Polar Research Institute scientists at their base on King George Island. Marine bird and mammal specialists led excursions to important penguin colonies to gauge the unfortunate decline in their numbers. The expedition climaxed with a sailed entry into the submerged crater of Deception Island: for now, a quiet volcano, (last erupting in 1967, destroying some scientific stations), with active thermal vents at its base. These vents pour mineral-saturated hot water into the ocean, not only precipitating a multitude of crystallized compounds, but providing a chemosynthetic foundation for unique life forms in the area. What is particularly interesting about this thermal vent system is its proximity to the surface, interfacing with photosynthetic- energy producing micro-organisms. The latter has never been carefully studied before. Dr. Dziak arranged to send a submersible, remotely operated vehicle to the site to capture video and still images that initiated the exploration of this unique phenomenon.

|

The extreme environmental conditions of Antarctica limits what can survive there, and very few plant species have been recorded on the 2% of the continent that is ice-free. They include about 150 lichens, 30 mosses, some fungi and one liverwort. Only two native vascular plants are known, as compared to the 100 or so flowering plants found from the Arctic. Of all the plants, lichens are the best adapted for the harsh climate. Because there is little competition from other types of plants, plus their high tolerance of drought and cold, lichens have proliferated in Antarctica (some even found within 400km from the South Pole).

|

|

|

As my previous work had, at times, contemplated the intersection of discovery and fantasy, the naturalist who places himself uncomfortably in a new terrain and attempts to relay his impressions, I experienced this invitation to be a, yet, higher threshold encounter with Nature. The Russian research vessel, Yuzhmorgeologiya, and its Korean and American specialists charted new sea floor activity, ice movements and that of the ocean fauna, but there was evidence of humankind already present by marine and atmospheric changes: artistically speaking, a very rich and urgent intersection.

|

Haru Matsumoto and Korean scientists working on one of

the Hydrophones in the ship’s lab. Once the high-pressure titanium cylinder is opened, computer data is downloaded and batteries are replaced to ready the instrument for another year in the ocean. |

|

Marian Cove icebergs off the shore of the Barton Peninsula (King George Island), and location of the Korea Antarctic

Research Program’s King Sejong Station. |

Video and photographic documentation, writing entries to a contemporaneous interactive blog, close assistance with deepwater sampling and instrument recovery, were all a piece of my participation in the voyage. More important is the legacy of the experience as manifest in subsequent discussions, lectures, art projects and presentations. Britt Salvesen, in her essay on my work at the Koehnline Museum, wrote eloquently about the relationship of science and art:

|

|

“Science and art both depend upon experimentation, but the status of these disciplines and their end-products are historically and culturally determined. Today, certain social, moral, political, religious, economic and literary discourses contribute to a tendency to oppose science and art. This polarization compromises both pursuits. The artist and the scientist share a concern with the as-yet-visible and unproven; both charge themselves with rendering the new kinds of experience they encounter. And both ultimately emulate the process already and always at work in nature.”

This is precisely why I paint. Dr. Dziak has been generous to invite me to join his team again to return to Antarctica and the Southern Ocean in 2010/11, and explore what may be the largest underwater thermal vent system yet discovered. With the broad and emergent awareness of global warming and it’s environmental consequences, changing life and events in the polar regions of the earth, plus the social and economic factors in our distancing from Nature in general, is a story that must be told; it is as much human, as it is scientific. |

Del Bohnenstiehl and Joe Haxel inspecting a topographical map of Deception Island, an active and partially submerged volcanic caldera in the center of the Bransfield Strait. Because of its nearly enclosed shape, the island has one of the safest harbors in Antarctica: a refuge from storms and icebergs. First used by sealers, a whaling station was later established there and operated in the early 20th century. Research stations suffered serious damage from two eruptions in the late 1960s; sub-aquatic thermal vents and fumaroles spewing noxious gases are still active today.

|

|

A Blue Whale jaw bone in a mossy flat just inland from the east King George Island shoreline. This species is the largest known animal to have ever existed on Earth. This relic is possibly a consequence of once heavy whaling activity in the region, including illegal Soviet harvesting. Worldwide population numbers remain at under 1% of their original levels.

|

Dr. Dziak and his team published a paper on the results of the expedition in the January 2010 issue of the JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH.

Tectonomagmatic activity and ice dynamics in the Bransfield Strait back-arc basin, Antarctica Authors: Robert P. Dziak, Minkyu Park, Won Sang Lee, Haru Matsumoto, DelWayne R. Bohnenstiehl, and Joseph H. Haxel In the Acknowledgements, the authors thanked me and my colleagues, B. Hanshumaker, T.-K. Lau, K. Stafford, S. Heimlich, M. Fowler, and S. Yun, for our at-sea support and laboratory assistance. Robert P. Dziak, NOAA/Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, CIMRS/ Oregon State University, Newport, OR, 97365 |

|

A portion of Andrew Young’s participation in this project was supported by the Illinois Arts Council.

|

Unlike the seals of the Northern Hemisphere, this sleeping Weddell Seal on King George Island has no land predators such as the Polar Bear to be wary of. They are deep-divers in search of a wide diet consisting of fish, krill, squid, bottom-feeding prawns, and sometimes penguins. Weddell Seals are vulnerable once off the shore or pack ice, however, potentially falling prey to Orca Whales and Leopard Seals.

|