Selected Projects

Indexing the World: invention, abstraction and dissonance

An exhibition conjuring our intricate and elastic relationship to the landscape.

The Art Center Highland Park, IL, April – June 2011

- Andrew Young, curator

|

In the summer of 2010, I was invited to guest curate an exhibition for The Art Center of Highland Park. The director of the Center specifically requested that I select a theme that would include at least several artists, including my work, for their Main Gallery. This would be my second project for their Exhibitions program and significantly more important for its timing would coincide with Art Chicago at the Merchandise Mart and the Center’s annual Gala Benefit in the spring of 2011.

|

Kim Keever, Forest 72D, 2007

C-Print, (ed. 6), 49 x 73 in. |

|

This project was also a collaboration with The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, as the Alumni Relations Office hosted a lecture/performance by Judit Hersko entitled Pages from the Book of the Unknown Explorer.

I would like to thank all of the participating artists, Richard Gray Gallery, Carl Hammer Gallery, Andrew Rafacz Gallery, and Carrie Secrist Gallery for their generosity in lending work to the exhibition. Stephanie Lentz, Mario Castrejon, and Efren Olivares of The Art Center were exceptional in their assistance to make this project happen. |

|

Thomas Cole, 1801-1848

Distant View of Niagra Falls, 1830 Oil on panel, 19 x 24 in. Collection of The Art Institute of Chicago |

Indexing the World: invention, abstraction and dissonance

In the early 19th century, American art went through a transformation in tandem with the view that the wilderness was no longer dangerous or untamable, and Nature represented as much a frontier as the more spiritual aspirations of our national character. Writers and painters turned to the landscape for inspiration, finding religious and philosophical content within the pursuit of something unspoiled, and unlimited. Thomas Cole (1801-48) was the founder of the Hudson River School of painting, which combined highly realistic detail with an idealized, even romantic, depiction of the land. Starting with observational and tactile relationships to their surroundings, the Hudson River painters brought home sketches and collected artifacts (sometimes photographs) to integrate in their works the physical aspects of a location with an essential mood and memory for the scene. |

Cole’s paintings, as well as those of his contemporaries and the next generation of American landscape painters (Bierstadt and Church), often portrayed nature with optimism: as an archetypal paradise and a new beginning for a society. It was a hybrid of both real and ideal notions of the natural world and our place in it. Less than 200 years later, artists make similar gestures and considerations in their work, spanning from the fantastic, perhaps dissociated, idealism of a place we know only in our thoughts, to more realistic representations of a two centuries-long assault on our environment.

|

Indexing the World: invention, abstraction and dissonance is an exhibition of six contemporary artists and one early photographer who employ both fictional and representational strategies to describe our intricate and elastic relationship to the landscape. Today, the limits of natural resources, urbanization and climate change are familiar themes that have made the public discourse about the earth specific to our utility and survival in an evolving world. Many artists respond to this with social and geo-political work. However, what is often displaced in this conversation is who we are in nature, how we see and what defines us from the outside in. There is something lyrical, rhythmic and almost scientific in the distance the artists in this exhibition create, not just in their chosen medium, but in the self-conscious “inventions” that inhabit their working processes.

|

Albert Bierstadt, 1830-1902

Among the Sierra Nevada, California, 1868 Oil on canvas, 72 x 120 in. Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum |

|

David Klamen, Untitled, 2010

Oil on canvas, 17 x 23 in. |

David Klamen paints landscapes from memory, with some evoking historical depictions. He layers upon their surfaces an optical grid of contrasting dots which delay and/or skew the unfolding of the image, almost creating an experiential – if not palpable – span between the observer and the observable. Photographic, as well as painted, scenes are rendered dark and layered, void and still; it’s as if our senses and imagination are intensified by the very elusiveness of the apparent subject. By virtue of the screens and depth, even surrealistically luminous frames within the canvas, the landscape and the viewer become equivalent subjects in the same story; the “space between” facilitates recognition of what is absent or present, conscious and unconscious in our experience.

|

|

Kim Keever uses large-scale photography to render – at least from a distance – convincing, rather painterly images in the traditional landscape model. Upon closer inspection, our initial assumptions of what we are seeing fall away and we are left with a visceral and visual echo of a place that never was. The setting of Keever’s “landscape” is really a laboratory, at the center of which is a large aquarium filled with many props and a variety of immiscible liquids that can be photographically captured in motion. It is a highly manipulated staging of a place, a “set” if you will, that evokes our notions of the sublime throughout history and what is transient or fleeting in us today.

|

Kim Keever, Wildflowers 51F, 2009

C-print, (ed. 6), 53 x 70 in. |

|

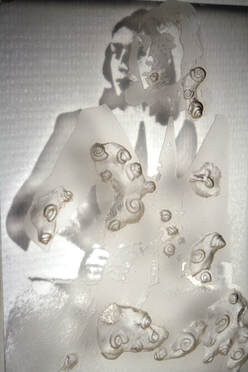

Judit Hersko

Portrait of Anna Schwartz (detail), 2008, silicone, 12 x 9 in. |

Judit Hersko collaborates with scientists who study elements of our changing environment in the South Polar region of the globe. Paradoxically, the name of the Antarctic continent alone evokes a sense of something frontier, heroic and forbidding, yet it is there that subtle, maybe irreversible human stresses on the planet manifest. Hersko inserts a fictitious female “Explorer” into real events in order to reflect on the gender politics of early scientific exploration and to present current data on climate change caused by human activities. Far from didactic, her contemplative sculptures and installations are as much about the ephemeral world – transience and memory – as they are about the human impact on the earth.

|

|

The photographs of John Opera seem at first banal and retreating. Without fanfare, it appears, the artist allows his subject to speak for itself – however quietly – and, in contrast with Keever, with few devices or play. Opera’s works straddle abstraction, the history of art through photography and the resonant features of our natural world. Be they a forest scene, a flock of birds or a straight-on shot of a black-out curtain, the literal presentations embody a mystery and a seeming symbolism for something larger than what we can see. The works as a whole describe a dynamic and somewhat philosophical relationship between our constructed notions of nature and the cosmic laws that define us.

|

John Opera, Forest, 2008

Archival inkjet print (ed. 5), 54 x 44 in. |

|

Timothy van Laar, Fountain, 2005

Printed materials on museum board, 5.75 x 14 in. |

Timothy van Laar’s constructions embody the essential “found” and intuitive aspects of collage art. Beginning as a photograph of a location visited and remembered, his Berlin postcards become odd messengers of things dislocated, lost or forgotten. Not unlike collections for study, these and other discovered graphic materials are souvenir fragment-representations of a landscape. No manipulation is made to the artifacts themselves; the photo postcard, the maps, illustrations and diagrams already suggest a translation of nature into a separate paradigm. When combined, even turned on end, new meanings are made or are alluded to – meaning not invented, but “unlocked” by a new language of association.

|

|

The mixed media works of Andrew Young hearken to a time when natural historians were artists as well as scientists. As with Cole and the Hudson River School, there is an impulse to find reverence with nature, as the known was supplemented with the imagined, and the banal became beautified. However, Young is aware that all collections for study are inevitably connected with the separation and disappearance of what is catalogued. His paint materials are hand-ground, often mined and processed directly from the earth, but the natural forms he depicts come purely from memory. More than a sensory imprint of “plant” or ground, they are abstract, even ghostly. Painting is at once a physical, tactile endeavor and a search for a lost sensibility.

|

Andrew Young, Boundary, 2011

Iron-oxide pigments hand-collected at The Grand Canyon and the salt mining region of Pakistan on museum board. 26 x 16 in. |

|

Wilson Bentley

Vintage photomicrograph, circa 1883-1931 |

In 1885, Wilson Bentley became the first person to isolate and photograph a single snow crystal. Remarkably, he was a self-educated farmer who went on to document over 5,000 “snowflakes” in his lifetime. Not only is the phenomenon of snowflakes evocative of scientific fascination and childhood wonder, but the manner and result of Bentley’s project seems to elevate this fact of nature to the iconic. He wrote in 1925, “Under the microscope, I found that snowflakes were miracles of beauty, and it seemed a shame that this beauty should not be seen and appreciated by others. Every crystal was a masterpiece of design and no one design was ever repeated. When a snowflake melted, that design was forever lost. Just that much beauty was gone, without leaving any record behind.” Bentley didn’t call himself an artist, but his process speaks to aesthetic notions and a singular pulse about everything.

|

|

The artists of Indexing the World: invention, abstraction, and dissonance connect with the natural world in any variety of media – be they photographic, painterly, or sculptural – and within each is a described intimacy for our relationship to the landscape. Coupled with this close encounter is a dual, seemingly self-conscious engagement, if not outright challenge, to the romantic notion of the sublime in nature. This is not a dichotomous or turbulent station, rather an evocative point of reflection, or meditation, on just how near or far we are from something essential in our experiential world, something undeniably part of us.

- Andrew Young |

Andrew Young, Coal Drawing, 2011

Bristol paper stained and painted with coal collected from Braceville, IL, shaft mine spoils (c. 1880s) on museum board, 22 x 16 in. |

© The above artworks may be protected by copyright. They are posted on this site in accordance with

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.