Selected Projects

Why Prevent Extinction?

Conference and Book Publication

Chicago Academy of Sciences/ Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, 2014

|

In the spring of 2014, the Chicago Academy of Sciences/ Peggy Notebaert Museum hosted a conference entitled “Why Prevent Extinction?” to commemorate the centennial of the passenger pigeon's disappearance. Though many species of our modern world have vanished over the past hundred years (some of them mysteriously) – not to mention episodes of mass extinction throughout Earth’s history – the passenger pigeon, whose flocks once numbered in the billions and could darken the sky for days, was flat-out hunted to extinction. This tragedy has since come to both incentivize and symbolize the present-day conservation movement. Sadly, since 1914 and the loss of “Martha,” our very last known living passenger pigeon, the rate of species extinction has only increased, many of those without much fanfare or even notice. Some have argued that this time in the history of life represents the Sixth Great Extinction. Whereas, in previous extinction events, researchers have found evidence of catastrophic loss corresponding to geological forces, such as asteroids or volcanic eruptions, what is happening today can be attributed mainly to human activity. The question, as put so starkly in the conference title, is should we do anything about it?

|

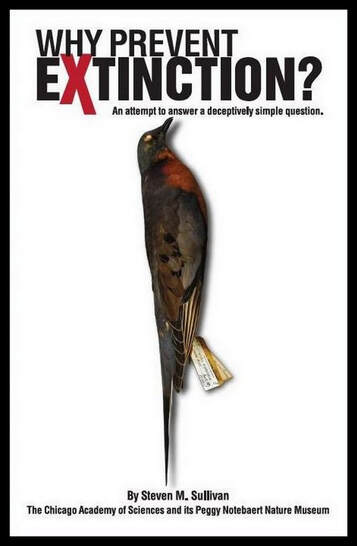

Book cover proposal for Why Prevent Extinction conference summary of proceedings, 2014.

|

For the purpose of the conference, the museum invited five experienced academics whose specializations could offer different and, at times, complimentary perspectives on the matter of extinction and the human position in its unfolding. May Berenbaum, an entomologist and professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, was asked to speak on the diversity of life. Joel Brown is an evolutionary biologist from the University of Illinois at Chicago whose work is grounded in mathematics. Jeffrey Lockwood, an entomologist and historian from the University of Wyoming, addressed shifting popular attitudes regarding our natural surroundings as well as the challenges presented by pest organisms. Curt Meine is a philosopher and senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation. Leopold is considered the father of conservation ethics. And Doug Taron is Vice President of Conservation and Research at the Chicago Academy of Sciences/ Peggy Notebaert Museum. With experience in habitat restoration and citizen science in urban environments, Mr. Taron spoke to preservation from a landscape perspective. Steve Sullivan, a naturalist and educator at the museum, organized the conference and moderated its panel discussions. My colleague, Joan Bledig, and I were asked to participate in every stage of the event, from devising questions for the round table and panel discussions, to note-taking during the presentations, and eventually to co-editing a summary publication about the conference.

|

Title Page proposal for Why Prevent Extinction book, 2014.

|

Biology and Conservation of Natural Resources was my declared major going into college back in the early 1980s. Though the focus of my studies and interests evolved over time and later, most curiously, landed on visual art as a professional practice, the subject of Nature – in particular the human relationship to it – has been a consistent concern in almost everything I do. I was fascinated by the seemingly simple question posed by the conference, but also understood the complexities involved in answering it. As a result, I jumped hard into my preparatory questions for the conference delegates, which I discovered said as much about the nuances (sometime conflicts) within my personal philosophy as they do about the difficulty in finding any agreement or fair resolution on extinction.

Many of the themes and concepts in my questions were woven into the conference proceedings. Steve Sullivan sought to integrate a write-up of the event with his PhD thesis at the University of Illinois, so I’ve decided to stay clear of his analysis and instead record my notes and pre-conference questions here in their naked form. Some of the remarks that follow are excerpts of our conversations during the conference that I thought were most relevant to the extinction quandary. |

|

Andrew Young: “Why Prevent Extinction” Pre-conference themes and questions, April 2014.

Part One – Note: These difficult - perhaps, cynical-sounding - questions and observations are coming from a personal point of view. I am not a scientist who studies wildlife and wilderness decline, but I cannot help but observe the human political/economic imperative and its oftentimes negative effect on the environment. Short of total global calamity, I am unsure what will compel large-scale correctives. I do, however, wholeheartedly commend organizations such as The Nature Conservancy, The Sierra Club, The Natural Resources Defense Council, Oceana, The World Wildlife Fund, The National Audubon Society and many others, including hundreds of regional and local agencies committed to education and conservation practices. Questions for the conference: 1. What is the generally accepted definition of species extinction and is it limited to natural populations or to all organisms, wild and in captivity? For that matter, as environmental degradation means that we as humans have become greater managers of even “natural” areas, what then defines “captivity?” Are we to be the zookeepers of all the Earth's living organisms? 2. It seems to me that a focus on the extinction of a particular animal can isolate it from the general ecology of its habitat. How are we to know or measure the significance of a species to ecological “health” before the system is far out of balance or before something has already taken its place? 3. In other words, the very system by which we list a species as “endangered” paradoxically separates it some from its role in the environment. In the conversation, less often do we hear about an animal’s value to the ecosystem than we do about how land must be cordoned off to protect the subject. This sets up a curious and, at times, contentious “land swap” mentality in the public imagination. Is it a strategy to save natural habitat with a sort of “symbolic conservation,” approach, using the face of a single, perhaps charismatic endangered species, versus a more generalized and laborious educational process addressing the vital importance of ecosystems as a whole? As a result, are people then allowed to pit their more pressing personal needs against the existence of one "inferior" animal, say, a bird or small fish the extinction of which appears not to affect them one way or another? 4. Can we assume that all species hold significance because they are already here? 5. Habitat destruction appears to be one of the greatest factors in reducing overall biodiversity. With global human population increasing, climate change putting pressure on once-rich agricultural areas, and standards of living changing in countries such as China and India, will the need for food production be the number-one impetus for habitat destruction and/or transformation? 6. The result of increased farming, of course, affects water supplies with pollutants such as pesticides and fertilizers; affects climate by releasing greenhouse gases in greater quantities than all vehicles – planes, cars, and trucks – combined; and affects forests by clear-cutting for workable land. Water is diverted and expended on crops, thus changing the natural systems surrounding. How do we balance an increased need to feed our world with the less popular notion of saving natural landscape for “some other reason?” Is the economy of human survival and enhanced standards of living more important than anything else? 7. I believe at the heart of what motivates most people, governments, industries, and societies is economics. We strive to live better and consume in the process. For the most part, this is the history of the civilized world. In fact, we wage wars to maintain the imbalances of consumption since it would be impossible for the whole world to consume on the level of the United States, Europe, and many other countries in their sphere. During our country’s leap into industrial, population, geographic, and economic expansion, we left a lot of destruction and many animal populations suffering, if not altogether disappeared. How do we reconcile our fairly recent history of reckless environmental habits and subsequent reform measures with the fact that China, India, and other countries now are going through their own version of “growth” such that air, land, and water pollution, and overall natural decay seem secondary to perceived increases in quality of living? Who are we to tell them they can’t have “growth,” even if it’s at the expense of habitat and animal diversity? 8. To the question above, is it a luxury to have a conservationist stance? The U.S. has the greatest output of carbon emissions in the world, but it condemns other countries for playing “catch up” to our level of consumption. 9. Back to extinction… From a purely utilitarian point of view, what good is an animal if you cannot eat it? Could we, in time, effectively replace the majority of the biomass on the earth with cultivated plants, domesticated livestock, and the matter that nourishes them for our consumption? Colorful birds and strange-looking hairy or horned mammals are exotic and interesting to look at, but in much of the popular view not much more. Are we so divorced from the earth by our psychology and technology that the globe and its dwindling animal array are at this point just one big zoo? 10. When we take out an apex (or top) predator from any ecosystem, we now know that an imbalance forms. Not surprisingly, apex predators in many cases are either competitors with our domesticated food-source animals or simply exotics easy enough and exciting enough to kill just for sport. Discovering the importance of an apex predator – say, a wolf – and trying to navigate the educational, economic, even mythological hurdles around its re-introduction can be an expensive prospect. (There was a recent backlash in Hawaii around a costly seal protection program which resulted in some “murders” of seals by disgruntled locals.) How do we create a consistent, non-political governmental authority for what animal, environment, or populace gets resources toward protection? What are the criteria and would it say something fundamental about our need to prevent things from simply going away? 11. Some people are resolved (or resigned) to the fact that "change happens." Over the millennia, many populations of animals have come and gone. Paleontology is primarily the study of life that doesn’t exist anymore. So extinction is in the fabric of the history of the earth: lots of it. But, as far as I understand, today we are seeing a rate of extinction more rapid than anything that can be ascertained at any point in Earth’s history. And, it is most definitely by our actions. What is it spiritually, or ethically, that tugs at some sense of responsibility for this loss? Is it, in the end, fruitless, ridiculous, or simply nostalgic to think we can slow – if not stop – the disappearance of various life forms on earth when it is not in our immediate economic interest? 12. Going out on a limb, here… I used to think a lot about what makes an individual conservation-minded. I could never come to a conclusion about whether it was conditioned (ie. developed/educated) or something having to do with an innate, life-long connection to things. At times, I would go so far as to think that a conservation-minded person could also be thinking about the environment like some kind of losing battle, say, a compassionate view toward an underdog. In the 50+ years of my lifetime, environmental destruction has been rampant, but so has consciousness – at least in this country - been raised. My question would be, is this consciousness really a minority viewpoint, and/or something “special” to occasionally entertain in the way that most people endeavor an adventure outside of routine but never fully incorporated into a lifestyle? 13. On a personal note, my heart is broken for what is happening to our environment, but I don’t know that this matters in particular. In fact, I don’t know why exactly my heart should be broken at all, except that I feel a certain wonderment, humility, awe, and connection when I am in nature: quite possibly all of the words and sensations most often attributed to a “religious” experience. I feel not above but a part of things when I observe how nature works, and I also sense its disappearance even when I can't see it happening. To allow an organism to go extinct must be symbolic almost more than any other measurable impact: symbolic to our growing disconnection with the land, and to a fate for ourselves that for now may only arise in our subconscious. I heard a quote once and I believe it was George Bernard Shaw who said it. It goes something like this: “Man’s inhumanity to man is only surpassed by his cruelty to animals.” Though we can never fully consult the victims of our environmental destruction, could it be they are also symbols of the pain we inflict on one another? 14. At the end of the day, I fear that, to most people, the energies toward preventing extinction are quaint, nostalgic, and/or wasteful. With increasing global population, climate change, and dwindling resources (not to mention the stubborn resistance to alter consumption habits, as well as the vigorous effort by others to increase their consumption habits), conservation practices will seem contrary to the most immediate of human needs and desires. The competition for resources – or the economic benefits of controlling them – will mean increased militarization, enhanced potential for conflict, and more peculiar rationalizations for such behavior. When freshwater becomes as rare and vital a commodity as certain minerals, some systems may be protected – say, guarded – and so too the animals that inhabit them. (Today, I understand 60% of China’s water is undrinkable. The Yangtze River dolphin is probably gone.) Are we just the most selfish animal with the fortunate capacity to keep it that way? |

|

Part Two –

Lest there be any confusion from my last set of thoughts and questions, I do consider Nature my church. The solemnity of my words regarding conservation is not wholly cynical (dark as they may seem at times), but pragmatic beneath the emotional. I cry for the animals of our planet as if I am in a painfully protracted state of “Goodbye,” and at the same time I feel marginally hopeful that dedicated communities will continue, and others brought around, in saving Earth's wonderful creatures. 15. Is there a term for a sort of “functional extinction,” whereby reproduction within a species or perhaps expanding its limited gene pool becomes near to impossible? 16. Doing anything that requires “sacrifice” on a purely volunteer basis or a cutting back in a growth- and consumer-oriented society such as ours seems to be a very tall order. Is it necessary then that protections be written into law, so that cities, states, nations, and the international community are beholden to these decisions regardless of costs? In other words, if not the person, who or what should be the regulating body and enforcer of rules, and is what we have sufficient or efficient? 17. I find that it is human nature to expand or contract one’s broader interests (especially if they come with a cost) based on deficiency (need) or abundance (excess). In other words, values appear flexible and not necessarily inherent or static. What does it take to make a core value – such as protecting a species or habitat – continuous, even in the face of wider sacrifice or disagreement? Need values and reflexive policy require consensus, a large or simple majority? Who are the arbiters of these values? 18. It’s interesting, and almost ironic at times, that we seek support from corporations and wealthy individuals to donate funds toward land preservation. Naturally, they have the money that enables the cause of conservation. But often these are also the entities leaving the largest environmental footprint. Could it be similar to a “carbon tax,” such that those who consume the most are also socially held accountable for its replenishment or repair? Perhaps beyond responsibility, the relationship can also be a means by which a general awareness is created around “cause and effect.” 19. As I mentioned above, I consider Nature my church. All of the attributes of a religious experience – humility, awe, connection, and compassion – exist for me in relationship to other organisms. The more passionate side of me, at times, would just assume give the world back to nature with a giant apology for humankind. A less dramatic – but no less costly – measure might be to consider ourselves as equals among species and try to cultivate a broader attitude of respect and sharing of the land. As with religion, could this be a purely ethical or “faith-based” orientation, and a perspective that transcends the utilitarian view? (It sadly appears that if something is not food or law, it has little bearing.) 20. In Part One of my thoughts and questions for the conference, I outlined the inevitable increase in global competition for natural resources as hand in hand with population growth. The human pursuit of natural resources will likely spoil, if not permanently reduce, habitat for other species. “Preventing extinction” will become more expensive and will be met with more popular resistance as the pinch of food scarcity increases. Might the rationale for conservation be best framed in terms of the human consequences – that which is environmentally interconnected and “best” for future generations – versus the protection of, say, a single flower or obscure insect? In other words, save the quality of the world for people and let plants and animals join us for the ride, as opposed to the non-anthropocentric view that one endangered species must have regional priority over all human activity? (I suppose it’s a language matter with identical goals, but not necessarily identical outcomes…) 21. And speaking of faith… Is it enough to know that an animal simply exists and survives somewhere in the world? If we cannot demonstrate a local or immediate human benefit, why work to save a species that none of us will ever see? (Of course, we don’t always know nor have the means to assess the ecological importance of anything usually until it’s too late. Should there be some enhanced variation of our current “scale of importance,” – ie., Endangered, Vulnerable, or Threatened Species List - or is this too subject to variable measuring techniques, cultural perceptions and differences, economic pressures, and simple prejudices like “cuteness”?) 22. Humor aside, I believe “cuteness” factors into what compels the public to think of loss and preservation. Aesthetically speaking, this is a very anthropocentric view of beauty on the planet. An “eco-centric” view of beauty may not have the trappings of cuteness or, for that matter, a relationship to structures and human expressions that already exist in the landscape, but still it can celebrate our coexistence with nature. Case in point, this country’s National Parks are more often spectacular and unusual landscapes considered “postcard worthy,” but similarly vital, less “beautiful” landscapes fall beneath the human recreation radar and are neglected or destroyed. How do conservationists convince people that land allocations unfit for human recreation or consumption are still vital to the overall health of the natural world? Or, how does a less-than-cute animal rank in the public imagination for preservation? 23. Demonstrating a human dependency on nature, in particular to those plants and animals out of sight and out of mind, can be a difficult task. Historically, religions have probably hurt as much as helped the cause of the defenseless in our world. For example, Buddhism is well known for its loving kindness toward all beings, including animals. However, the doctrine of karma implies that souls are reborn as animals because of past misdeeds. Animals’ inability to improve their spiritual lot led early Buddhists to think that non-human animals were inferior and had fewer rights. Similarly, early Christian thinkers believed that human beings were superior to animals. It was thought that humans could treat animals as badly as they wanted because there were few, if any, moral obligations to do otherwise. It was taught that God created animals for the use by human beings and that they were distinctly inferior because they lacked souls and reason. So this begs the question as to whether modern religious thinking has “leveled the playing field” more in terms of moral balance. Perhaps we are, indeed, custodians of the helpless, or are we so ecologically intertwined that an interest in animal survival stems mainly from helping ourselves? 24. Then we have politics… Ever since Ronald Reagan, the term “environmentalist” has been associated with anti-industry, anti-American, liberal extremist views. I remember him saying in a press conference that environmentalists wanted to turn the White House into a “birds nest.” Asked about setting aside forests as wilderness, he replied, "How many trees can you look at?" He and his administration then proceeded to unwind all of the EPA regulations that were perceived to stand in the way of conservative social, cultural, and economic progress. It was probably one of the most successful and destructive propaganda campaigns in U.S. government history to dismantle progressive (and I think now understood to be valuable) land laws and regulation. Movements such as Green Peace, which were an evolution out of the civil rights and anti-war protests, took a reactionary stance and increased their intensity proportional to more extreme government policies. So, this begs the question again about whom and what should be the ultimate expression of preservationist ideals, and what body should enforce them. 25. Lastly, are the interests, need, and commitment to species preservation also in some ways a vessel for social justice? I find the two almost inseparable. The history of humankind is rife with taking land and resources from one another to serve the interest of the “winning” side. Today, there is very little collective or global agreement, much less cooperation, on conservation policies. It may be demonstrative – and also magnificently ironic – that one of the most successful examples of restored landscape and biodiversity happens to be in the “no man’s land” DMZ border between North and South Korea. Few, if any, human beings set foot in the band that separates the two countries technically still at war and in truce since 1953. This 150 x 2.5 mile swath is a rich and dynamic ecosystem – bountiful like no other place in either of the Koreas – where everything is protected by fences, mines, guns, and uncompromising politics. The two countries are among the world’s worst by way of environmental records, so the safety of endangered species in this case is almost purely accidental and wholly dependent (and sadly ironical) to the continued tensions between the countries. What a statement about the human condition and the future of life on earth. |