Selected Projects

Book Cover

The Fall of Cities in the Mediterranean

Commemoration in Literature, Folk-Song, and Liturgy

Edited by Mary R. Bachvarova, Dorota Dutsch, and Ann Suter

Cambridge University Press 2016

|

In 2008, I was a guest at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America held that year in Chicago. (Founded in 1879, the AIA is a North American nonprofit organization devoted to the promotion of public interest in archaeology and the preservation of archaeological sites.) There, I met many fascinating people, including Ann Suter, Professor Emerita of Classical Studies at the University of Rhode Island, who had just completed a book titled Lament: Studies in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 2008). She and her colleagues, Mary R. Bachvarova, Professor of Classical Studies at Willamette University, and Dorota Dutsch, Associate Professor of Classics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, were working on a companion volume called The Fall of Cities in the Mediterranean: Commemoration in Literature, Folk-song, and Liturgy (later published in 2016 by Cambridge University Press). Whereas, the first book analyzed various ancient literary sources to consider individual lament, this new collection looked at mourning on a larger, less frequent, and more societal scale: for example, the communal trauma from the destruction of whole cities or populations.

|

Around the mid-1980s, I took some college courses in Classical Archaeology during a period after studying abroad and when my major focus was shifting from science to the humanities. To hear Professor Sutor speak of her latest work, especially in reference to Homer’s epic poem Iliad and its setting of the Trojan War, I felt something of a déjà vu experience going back twenty-plus years. She learned I was an artist in that conversation and later saw some catalogs of my paintings. This led to an invitation to submit a proposal art piece for the upcoming book’s cover, something full-circle to me. Needless to say, I was ecstatic, if only to be just a tiny part of this exciting project. Troy seemed like a good place to start.

The probable location of the ancient city of Troy.

The legendary ancient city of Troy is in western Turkey and strategically located at the mouth of The Dardarnelles, one of the world’s narrowest natural straits and part of the continental boundary between Europe and Asia. It was a bridge between cultures and its position critical in controlling trade routes to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea. In Homer’s Iliad, the Trojan prince Paris mentions to the Spartan king Menelaus that the city regulated access to Indian silks and spices. Troy’s history dates back to the Bronze Age and remained an important commercial center and settlement for thousands of years. The Late Bronze Age – around 1300 to 1200 BC and the time of the famed Trojan War – was an era of powerful kingdoms and city states surrounding fortified walled palaces. Kings largely controlled commerce which was based on a complex gift exchange system between various political states. Mycenaean city states based in present-day Greece were also competing with the larger Hittite empire (which at its peak included modern Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey) for command over the trade routes.

|

Ancient ruins of Troy.

|

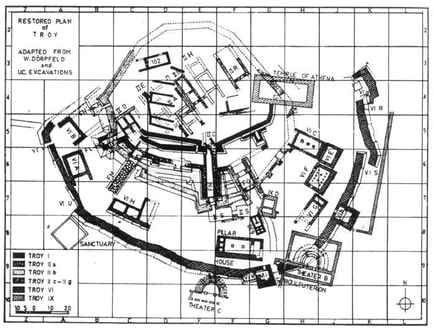

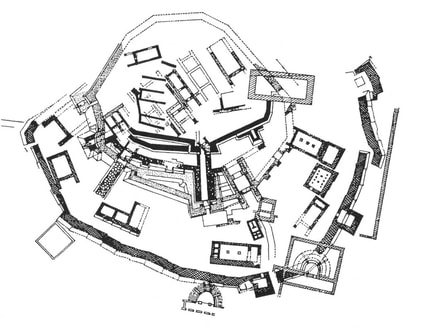

Over the last 150 years, the ruins of Troy have been painstakingly excavated. Though first visited by a Westerner in 1547 (a French government official named Pierre Belon), the full extent of the ruins came to light only when German amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann conducted a series of large-scale excavations there between 1870 and 1890. Schliemann was convinced that Homer’s Troy was located in the area known as Hisarlik and evidence from his digs confirmed his assumptions. Unfortunately, his lack of respect for the site and poor methods led to the destruction of much of the data that would be scientifically and culturally valuable today. Further, many of the treasures that were found were taken out of Turkey illegally and are to this day a matter of contention. What Schliemann didn’t recognize at first was that he wasn’t just excavating one city of Troy, but numerous, different cities that were built, flourished, and then declined, all at the very same place. The site is ultimately composed of nine different layers representing nine separate city installations. This demonstrates a rich diversity of civilization dating from 3000 BC to 1200 AD: from mythological Greek to Byzantine times.

|

|

It was on Schliemann’s last 1890 excavation (and several later excavations by German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld in 1893-94) that suggested the layer, Troy VI, should be assigned to the Mycenaean period when the Trojan War was fought. Archaeological and historical research in the eastern Mediterranean basin appears to confirm Homer’s account about the war, or at least when he says it occurred. Whether an affair between Prince Paris and the Spartan queen Helen triggered the conflict is uncertain, as is the conquering of the city only when Greek soldiers hid themselves within a giant wooden horse to gain access. However, contemporary sources from the Hittite archives in Hattusha do describe military campaigns by Greek kingdoms around the same time, mentioning raids and mass kidnappings for the slave trade. There is a record of a peace treaty between the Greeks and Hittites regarding Troy as well. This period witnessed ruin throughout the Mediterranean basin. Once prosperous Troy, as well as the wealthy Greek cities Mycenae and Tiryns, were plundered, destroyed, and ultimately abandoned. These “falls” were so poignant, so impactful that the cultural memory of them lasted for centuries. In Classical Greek mythology, the story of the destruction of Troy was recorded by Homer 400 years later in two epics poems: the Iliad and the Odyssey.

|

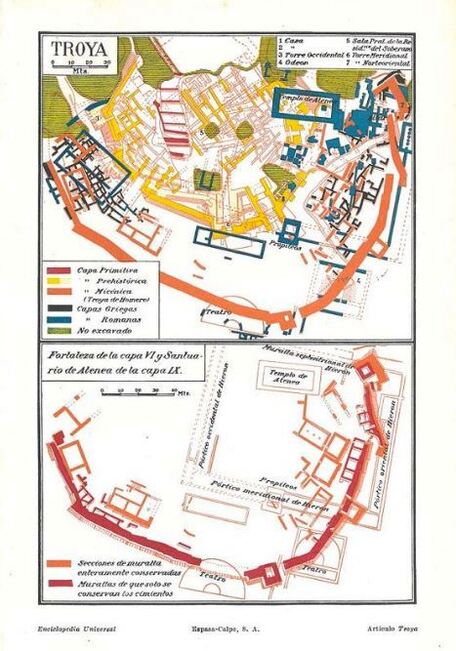

Two maps of the historical city of Troy, circa 1920s. The upper shows the layers of ruins at the citadel, the lower map depicts the fortress of layer VI and the Sanctuary of Athena.

|

For the purpose of the book cover project, I asked Professor Sutor to send me an archaeological plan of Troy, not just for the 5,000 years of history it represented, but for its abstraction in form: the familiar boxes, curves, and repeating lines of age-old structures like temples, theaters, and fortifications. I decided to digitally rid the map of its grid spacing and any notations, and let the scar of the ruins be the foundation for a painting. Since the book was about communal grief and commemoration for large-scale loss, I thought to integrate something of nature (which itself has cycles of life and death) with the architectural skeleton – something floral, perhaps with a suggestion of ritual or the funerary. It was done in mixed media, primarily of hand-ground watercolor and gouache paints made from ores. And, as with archaeology, the built up surface was scraped back, as if to hint at time, layering, concealment, and reveal. The resulting artwork was accepted and appeared on the cover when the book was published in 2016, a full eight years after my initial meeting with its authors.

Restored plan of Troy's citadel adapted from W. Dörpfeld's excavations. The successive

archaeological and urban levels are noted. Note also the outer and inner walls of Troy VI.

archaeological and urban levels are noted. Note also the outer and inner walls of Troy VI.

This year, 2020, and for the purpose of this writing, I re-read Professor Sutor’s introduction in the book and was moved at how relevant the findings regarding ancient historical memory and communal trauma are to our collective experience today. Loss is loss, and memory of it travels through the generations like water in the ground: sometimes fast, sometimes slow, even mutating, but always finding its way. She and her colleagues studied many varied expressions of ancient grief and sorrow. The causes over centuries, however, appear similar. I was compelled to write her this email communication:

Dear Ann, In light of our current political climate and health crisis, I’ve been thinking a lot about your 2016 book, The Fall of Cities in the Mediterranean: Commemoration in Literature, Folk-song, and Liturgy. (Thank you again for the invitation to lend some artwork to its cover.) They say that history repeats itself, or perhaps the human characteristics of aggression, denial, division, and despair will always be lingering components of greater tragedies. I’m curious how we will look back on this time, especially as our losses become larger and our collective mourning ever-present. My 85-year old mother, for example (a retired English teacher and drama coach) is conducting Zoom book-reading meetings with themes that almost always touch on the grieving process. Perhaps we are looking backward, too, in an effort to find a footing for dealing with the future unknown. I think your introduction in the book is brilliant and prescient. I’m inclined to dig deep into the main text. Again, thank you for allowing me to be a very small part of your excellent project. I trust you are well and look forward to the possibility of connecting again. Best, Andrew.

Dear Ann, In light of our current political climate and health crisis, I’ve been thinking a lot about your 2016 book, The Fall of Cities in the Mediterranean: Commemoration in Literature, Folk-song, and Liturgy. (Thank you again for the invitation to lend some artwork to its cover.) They say that history repeats itself, or perhaps the human characteristics of aggression, denial, division, and despair will always be lingering components of greater tragedies. I’m curious how we will look back on this time, especially as our losses become larger and our collective mourning ever-present. My 85-year old mother, for example (a retired English teacher and drama coach) is conducting Zoom book-reading meetings with themes that almost always touch on the grieving process. Perhaps we are looking backward, too, in an effort to find a footing for dealing with the future unknown. I think your introduction in the book is brilliant and prescient. I’m inclined to dig deep into the main text. Again, thank you for allowing me to be a very small part of your excellent project. I trust you are well and look forward to the possibility of connecting again. Best, Andrew.

Andrew Young, Fall of Cities book cover proposal artwork, 2012.

Below, with special appreciation to Cambridge University Press, are a couple of short excerpts from Professor Ann Sutor’s book introduction. Somehow, these words resonate for me as our country, today, appears to be at a threshold – say, existential – moment about its core identity and direction.

|

Cambridge University Press, 2016.

|

Chapter 1, Introduction - Ann Suter

This collection on commemorating fallen cities follows naturally in the wake of our 2008 collection on individual lament (Suter 2008). We have discovered much that is the same in the reactions to the death of a person and the demise of a city – for example, the desire to keep some memories alive, the wish perhaps to remember and maintain the animosity towards the forces that destroyed the person or city. But more interesting has been to discover the differences. Individual lament, although occasioned by a sad event, is not an impulsive expression of personal grief so much as a carefully ritualized emotional outlet and a vehicle for managing an unexpected, but common, event. Mourning for the destruction of whole cities or populations, on the other hand, happens only infrequently, and has never developed a traditional form, but is expressed in numerous ways: epic poetry, drama, liturgical lament, folktale, to name a few covered in this volume. Nevertheless, mourning for a destroyed city, whatever its literary context, came to use common “structures, patterns, and types of discourse “ – including the city lament proper as a literary genre – in the course of accomplishing its unique purpose: to address “communal trauma, grief and memory, and as a memorial act” that “shapes historical memory.” (It is) ....connected not just to memory-making, but (also to) memory sharing…, for individuals and communities.”

|

It is the purpose and interest of this collection to examine some examples of this special kind of commemoration, and how the motifs recognized as referring this particular modality of remembering past events were exploited and manipulated in a variety of literary and folk genres in the eastern Mediterranean from the beginning of the second millennium BCE to the beginning of the twentieth century CE.

We would like to add this collection of “falls” to the study and methods of commemoration. Whether or not they originate in an actual historical event, these commemorations always differ from History as conceived of in modern academe chiefly in their sense of why the past must be remembered: it is to commemorate and glorify something that was thought to be gone forever: that something might be a city, a group of people, a culture. It could commemorate a destroyed physical location or a community of people. Rome provides an interesting case study, since no one ever admitted that Roma aeterna * ever fell. Rather, its importance as a city devolved on other cities in the empire, and it became simply a symbol of past glory, just as it co-opted the past glory of Troy and Alba. Here we see a model different from the Mesopotamian conception of world rule pass as an inheritance from one great city to the next upon the destruction of that city.

|

The Roman tradition is idiosyncratic: it has little to do with the gods as a cause of Rome’s fall, perhaps because Romans until the end denied that Rome fell. The tradition’s essential tenet was that Rome was destined to rule other nations and therefore could not fall. Perhaps for this reason, Romans were interested in the fall of other cities as an opportunity to philosophize on Rome’s situation.

|

* Coining the phrase Urbs Aeterna, or Eternal City (which later spawned the phrase Roma aeterna), Tibullus was responsible for starting the trend among Romans of thinking of their city as the pinnacle of society – if Rome fell so would the rest of the world.

© The above images may be protected by copyright. They are posted on this site in accordance with

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.