Selected Interviews

Portrait of an Artist: an Interview with Andrew Young

Entre Nous (Midwest Organizational Learning Network), July, 1997

- Roger Breisch, with Joe Triolo

|

The paintings of Andrew Young bespeak a haunting, yet poetic lament for a nature idealized and for a pictorial system based on human experience. Like others before him, Young’s search is an aesthetic one, a journey where the past and the present, the illusionary and the abstract meet and intertwine.

- Susan Snodgrass, Chicago, 1992 Andrew Young is an extraordinary young artist who has taught and exhibited around the world. He recently joined MOLN. Roger: Andrew, why are you an artist? Andrew: That’s really the ultimate question. Making art, if that’s what being an artist is, is kind of a pretentious act in a way. Like actors, painters create an artifice through which to engage something that would normally terrify us. It’s pretending, but also a medium of expression that, for me, addresses the deeper life, soul, and heart questions. I chose, at some point in my life, to make a world, if you will, a career, around the endeavor to delve into, swim in, or wrestle with some of those deeper issues. Art almost forces them on me. |

Five Fish Feeding, 1990

Egg tempera on wood panel, 35.5 x 27.5 in. |

|

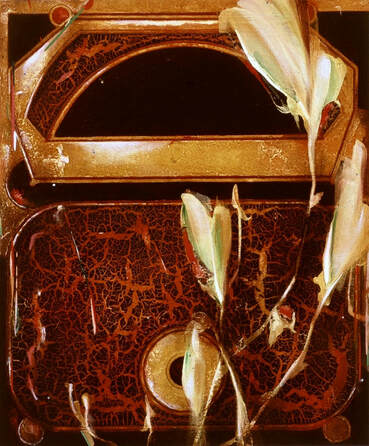

Roost, 1990

Egg tempera on wood panel, 13.5 x 11.5 in. |

Roger: So how did you come to discover that this was your life’s work?

Andrew: Well, I sort of had the best of both worlds. The household in which I grew up had a strong orientation to visual and performing arts. My mother studied dramatic art in college and is a stage actress. She is currently an English teacher and director of a theater school. We also had in our home paintings by her. Paint, pencils, papers and things like that were not unusual; they were part of a mix in a way. My father I would fashion more as a connoisseur of art, a collector, someone who is deeply involved in theatre, opera, symphony and museum going… a world traveler. From every city he visited I received a clipping kit, a packet of brochures, post cards and posters, sometimes artifacts….the spoils of his investigation. The curiosity to see and contact the world that way is something that influenced me early on. In college I had a very strong love for art but didn’t feel it was appropriate to pursue it full time; in fact, I was very much afraid of it. I had a strong affinity for sciences as a way to understand our environment. Then, in my honors thesis, I wrote that so long as we define nature as something separate from ourselves, we defy our very ability to understand it. Art was an attempt to embrace the very human bias that science attempts to eliminate. |

|

I had a lower drawer at my desk, sort of my “altar”, filled with pastels, watercolors, watercolor pads and colored pencils, all of which were impeccably arranged, neatly sharpened and color-coded. Periodically, I would go back into that drawer and polish the instruments…like I was preparing for something. I had no awareness at the time I was going to be a professional artist.

Three semesters in succession I signed up for and withdrew from a course in color and composition because I knew what kind of door it would open. At the risk of sounding arrogant, I suppose I knew I had something; I knew I had a great deal of passion for the subject. I was almost like a closet art lover: reading magazines when I should be looking at something else, going to art museums when I said I was going to a sporting event. I was trying to conceal something that was clearly boiling in my spirit. As far as the soul and the things that I recognized could be explored and expressed in art, the power of that relationship was overwhelming. Roger: What other kinds of pressures did you face to keep you out of this and into a more normal profession? Andrew: Even your question suggests a certain stereotype or perception about the abnormality of being an artist. It might be surprising just how similar my day-to-day life is to a lot of people who run any business. But there is a stereotype about being an artist that makes some people suspicious of the field. |

Orange Lips and Green, 1992

Egg tempera on wood panel, 15.5 x 13 in. |

The pressures upon me were in trying to make a decision about how closely I fit to a “misfit” kind of identity, because that’s the way society looked at it. As an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, I was excited, quite vigorously pursuing a science major and was successful. I received a lot of positive support for that kind of work, though internally I was trying to find a stronger identification with what I did. Maybe everybody longs for the identification.

|

Toys Already, 1992

Egg tempera on wood panel, 27 x 17.5 in. |

It was a great change to go from what seemed like a fairly linear path—milestones, hoops and hurdles—into a field where those constructs are sometimes very nebulous. I was entering a world of writing my own script and I didn’t know exactly how to approach that. Art school, you would assume, would prepare you people for the world of self-employment, self-direction, etc., but it’s actually fairly flimsy. So that was a shocker.

Roger: Tell us about life as a starving artist. Andrew: Van Gogh blew it for us because, by him, we developed a romantic view of the struggle. I might be more successful if I had a more of a business attitude insofar as tapping into market demands, but I have a tenacious attitude about the search. Art has got to dislocate, disturb or mystify me, to some extent, to pursue it. So I embrace the myth, the romance of the struggling artist. I feel fulfilled by the struggle. Starving implies something more related to financial needs. I see how easily exploitable artists are because, since we are doing it for the love of art, it’s not given respectability or stature as bonified work. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had agreements and contracts defied, disobeyed or betrayed with the confidence on the other end that somehow I will deal with it. Within the hierarchy of the art world artists are definitely the plankton of the food chain. |

I had a conversation in Atlanta with somebody who was complaining about the striking symphony. His comment was, “They’re privileged anyway. They get to do what they want”. I thought, should we take a survey of all employed individuals and those who like their job more take a pay cut? If there is a strong ingredient of love or identification for what you do, should that be factored in as part of your reward, part of your compensation?

|

A lot of times that’s how I justify living the way I do and for what I do. There are a lot of artists who are not as fortunate as I am who have no commercial or gallery representation. The question becomes, what is the impetus for their working? If it is something larger than material gain, then that may be the ingredient to their success. Commercially, and I think intellectually, the art world is hungry for this kind of spirit, a phenomenon we call “Outsider Art”. I think that’s where the image of a starving artist appears because it’s both enviable and pathetic.

Roger: What else besides money have you given up in your lifetime? Andrew: I haven’t given up money! I strive for it everyday and I probably enjoy it as much as you do. I can have a great year and I can have a bad year. I have to deal with the uncertainty that comes with never knowing when or how I am going to be paid for what I am doing. I have positioned myself to make my artistic pursuit a more total experience: integrating my life in the studio, my life at my desk, my life on the telephone, galleries and international art fairs. To embrace all facets—commercial, public, private and deeply personal—of the art endeavor. |

What She Leaves Us, 1992

Egg tempera on wood panel, 23.5 x 20 in. |

What have I given up? I suppose the familiar criteria of success; the milestones we create in our lives. By a certain age the norm is to have so much money in the bank, so many walls around you in a home setting, a vehicle that goes zero to sixty in a certain amount of time. There are all kinds of measure any of us could readily address.

Sometimes I shudder in the morning when I wake up realizing the fragility of this process and knowing that I am reinventing myself every day. But that’s also the security in a sense because we attach ourselves to our job titles, to the larger company for which we work. In this case, I am the company.

Sometimes I shudder in the morning when I wake up realizing the fragility of this process and knowing that I am reinventing myself every day. But that’s also the security in a sense because we attach ourselves to our job titles, to the larger company for which we work. In this case, I am the company.

|

Hide the Eggs, 1993

Egg tempera on wood panel, 40 x 31 in. |

Joe: Can you see yourself in a normal job? What would that feel like?

Andrew: I’ve been in a lot of normal jobs, from bank teller to mechanic and pump jockey… grounds keeper at a country club to scuba diving (retail and instruction), waiting tables, teaching and laboratory work. What was pressing was the realization that what I desire is play, investigation and development: a delving into creative chaos, that nervous sort of openness or abandon. Don’t we all, in a way, long for that, and create that in our lives in different ways? Some people go to extremes in sports, ski down mountains at 150 miles an hour to create a rush. Well, I had a taste for this kind of intensity and I thought, it is worth the risk? Is it worth the chance to make that a more central part of my life? Joe: So this is something you have to do. Andrew: I don’t think I have a choice now. It’s a life sentence. Initially, the mechanical aspects of making it a profession were probably a greater unknown than the passion. I would argue that endeavoring to do something with these kinds of uncertainties, the kind of risk involved…if it doesn’t start in the heart, if it is not known inside, then the disappointments and the hazards on the outside will become overwhelming. |

|

Roger: Any regrets?

Andrew: Most of the time I feel very fortunate. There are a number of people who believe what I’m doing is essentially a good thing and I think that’s pretty incredible. So in that sense, it is hard for me to justify any complaints. I can play every day. I have some regrets and the time and yet, I wonder how on earth I ever found myself in this place. Probably the largest regret is that it is a business. I have positioned myself to engage the business aspects of buying, selling and trading art. I have to accept that though I regret I have allowed those externals to corrupt, to disappoint for frustrate the creative vision. My imagination and instinctive inclinations have been somewhat arrested by the deceptions and politics that probably exist in every business. However, they seem more acute when the product of my self-employment is a personal matter. I don’t regret being a businessman; in fact, I think I’m very good at it. I just think that is has invaded the sanctuary and the purer vision of the studio. Joe: So one of your principles is to protect creative process from the corruption of business. |

Rain Softens, 1994

Egg tempera on wood panel, 24.5 x 17.5 in. |

Andrew: I don’t want to summarize business as wholly corrupting. I’d say, corruptive in the sense that it can effect unwanted change. It is what it is and I’m beginning to accept that more readily. I realize my responsibility going into it. I actually adore a lot of the people I work with. Some of my favorite people are gallerists who probably feel they succumb to the same issues when the premise of their being involved in a gallery is their love of art.

|

The Red Tree, 1994

Egg tempera on wood panel, 31.5 x 23 in. |

Roger: What exactly does your art mean to you?

Andrew: A core belief of mine, and that which I think distinguishes me from a lot of other artists, is that there may be, and probably is, something universal about a human experience. The context determines how we interpret, how we act, our cultural history, the distinctions between societies and races, political histories. A lot of artists make as a central theme social, political commentary, where it’s topical, it’s of a certain time, maybe designed to invoke a certain change. Visual language is very potent, very powerful. Museums have been picketed and shutdown, museum administrators fired for the fact that there was so much public outcry over specific imagery. My goals address something more fundamental, more universal, but risk being almost nothing at the same time. In abstract art the formula is color, shape, composition, etc. It creates content, or a mood or feeling in their arrangement alone without being referential necessarily, without being narrative or specifically symbolic. Then, that which is being conveyed is very ephemeral, hard to identify and probably for each individual something different. I am interested in the way the viewer comes to a panel, with certain expectation, a certain kind of desire in a way to learn or to embrace something divine. |

I consider painting an arena for that moment. A human element played against the architecture and the structures which represent those patterns in our lives, the scaffolds, the kind of rules we make for ourselves. I think all of us live somewhere between the laws we perceive, the pre-ordinations into which we try to find fitness. And yet I think the real experience of being human is actually quite accidental…quite dynamic. We work most of our lives creating that which is usual, though we always seem to want a break from it. We desire the mistakes. We always talk about that unfortunate thing that happened…but wasn’t it kind of spectacular? I find most people laugh at, enjoy or find exhilarating even the danger in something that happens quite by chance.

|

Both by material and by image I try to set up dichotomies which are the parameters of our life experience. My paintings are made of egg tempera—egg yolk mixed with crushed rock—on top of a wood surface. So it’s organic and mineral in composition. I carve into the surface. They’re physically manipulated which brings a very terra firma, terrestrial basic or banal kind of reality to the paintings. And yet by color and form, and by some of the historical references, they make a kind of spiritual allusion which has always been the hopeful part of a culture, if you will, the desire. The mortal, terrestrial banal delivered by a certain kind of hopeful and spiritual quest. I think those are pretty much the parentheses of our experience.

Roger: How do you feel in the midst of creating or when you are finished with a piece? Andrew: I think everyone can recall, at some point in their experience, when we’re meant to write a great paper. It becomes a terrifying monster; even jotting down that first sentence becomes the most incredibly difficult thing to approach. Writing a paper about any subject is also putting down something of oneself. Painting for me is similarly terrifying; after all these years it is very, very difficult. It is inevitable that it speaks some kind of truth. It doesn’t lie. It’s responding precisely to my mood, my level of confidence. I bear 100% responsibility for every gesture, mark and color choice I make. |

Reading the Night, 1994

Egg tempera on wood panel, 47 x 29.5 in. |

I really don’t know where the creativity begins or ends. Just because I am involved in the act of painting, does that mean that it is necessarily the creative moment? Or was the creative moment walking down the street and deciding, “My God, I’ve got to do a vertical line because that’s where it’s all going to happen!” I think that eureka moment and the euphoria that comes aren’t necessarily specific to the event of laying paint on panel. Sometimes that’s just the execution.

A painting can never be finished without it impacting me deeper than any conscious decision. It is almost like snipping the umbilical cord; it has an identity of its own whether I like it or not. I almost have no say at that point. There’s some euphoria, a kind of exhilaration that’s attached to the discovery of what may have felt unresolved in my mind: the collision of things that previously made no sense, coming together seemingly on their own.

|

So Many Leaves, 1995

Egg tempera on wood panel, 29.5 x 23 in. |

Joe: Do you know what the finished painting will look like when you start?

Andrew: No, never. I have an idea of what I want, and a feeling I want to accomplish. In a way a painting always falls short, or is something other than what I originally expected. Yesterday, a comment was made to me that there is a certain lack of resolution in my work. Like a search element, transience is still intact and is somehow documented in the painting. As I’m working on a painting horizontally on the floor I’m hovering over it. I am very physical, moving back and forth, almost like gardening, troweling, trying to pull some kind of life out of something that is only somewhat cooperating with my attention. By the end, the experience has to touch on that which maybe I felt in the beginning, because that’s where the finish is, that’s where the recognition is made. If that image goes into the world, I’m banking on recognition as the connection. When somebody approaches it, they don’t know what I’m thinking but they might feel something in the painting which has a deeper, almost gut level excitement or impact. That’s a connection, that’s a recognition that’s made. |

Joe: So when you start, you are starting a process of discovery and exploration with some idea of where you are going, but you have to be ready…

Andrew: You have to be ready for the new moment. How do we keep ourselves open to that possibility without making it so dangerous, and so uncertain? I have more of an idea of what ingredients create the possibility of that newness, or whatever that moment is we are talking about. Maybe this is what distinguishes me, only by a degree, from most people. I think all of us have those discovery moments and the euphoria attached to it. I’m just trying to make some kind of physical document of that experience that’s transferable, that’s meaningful and accessible to others.

Andrew: You have to be ready for the new moment. How do we keep ourselves open to that possibility without making it so dangerous, and so uncertain? I have more of an idea of what ingredients create the possibility of that newness, or whatever that moment is we are talking about. Maybe this is what distinguishes me, only by a degree, from most people. I think all of us have those discovery moments and the euphoria attached to it. I’m just trying to make some kind of physical document of that experience that’s transferable, that’s meaningful and accessible to others.

Roger: Is it difficult to part with a piece of artwork that’s meaningful to you?

Andrew: Early on, painting and I had something of a personal contract which has changed over time. The strong autobiographical component of my earliest work, which had no audience consciousness, later became kind of a bonding agent, a letter, a voice mail, a vehicle for some kind of expression. Before that point, painting might have been akin to keeping a private journal that was only mirroring my confidence, insecurity and investigations.

Andrew: Early on, painting and I had something of a personal contract which has changed over time. The strong autobiographical component of my earliest work, which had no audience consciousness, later became kind of a bonding agent, a letter, a voice mail, a vehicle for some kind of expression. Before that point, painting might have been akin to keeping a private journal that was only mirroring my confidence, insecurity and investigations.

|

Parting with work addresses the issue of the audience or an intended viewer and the exchange between us. I know it is part of the process, but I’ve never gotten entirely used to it. The irony is that a “personal vision” suggests a particular isolation from the world and, yet, it is a digestion and interpretation of experience. It is at once engaged in everything and separate from everything. The studio serves as a kind of sanctuary where I can have the experience, late at night, that everything else is everything else. I imagine also that someone can enter this environment, engage a product of this place and feel what it is I am feeling. That would be an ideal scenario, but I only find a little, rare particles or incidents of this kind. Once a painting leaves the studio, the context, and therefore the meaning is changed forever. I grieve in some small way any painting moving into the public arena, because it’s both a form of vulnerability and also an evolution.

There is a longing in me which has changed over time. Where once there was completeness about the autobiographical component, now there is a longing for connection. Not until a painting is finally home or received does it feel complete to me. |

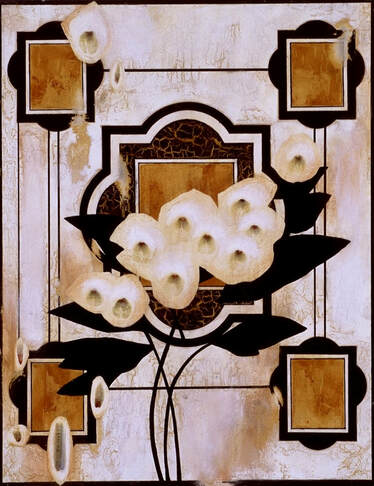

Unlooked-for Logic, 1996

Egg tempera on wood panel, 44 x 32 in. |

Roger: So tell us where your inspiration comes from.

Andrew: I have this overwhelming drive to do something different, different than I have ever done before. In between every assignment, every big show, there is this incredible space in which my imagination runs wild and I can think of a thousand new paintings…the greatest images of all time…something probably unachievable in real time and in real terms, but it’s the imagination opening wide. When it comes down to cracking the eggs, sorting out the crushed soil and rocks and various pigments, the very banal features of the act of paining, ninety-nine percent of that imagery washes away. I can’t access it. I don’t have the courage, the means or the time. All the other insecurities, the other practical matters start to impede. But, if I have made on increment of change by this process, then I consider myself successful.

Andrew: I have this overwhelming drive to do something different, different than I have ever done before. In between every assignment, every big show, there is this incredible space in which my imagination runs wild and I can think of a thousand new paintings…the greatest images of all time…something probably unachievable in real time and in real terms, but it’s the imagination opening wide. When it comes down to cracking the eggs, sorting out the crushed soil and rocks and various pigments, the very banal features of the act of paining, ninety-nine percent of that imagery washes away. I can’t access it. I don’t have the courage, the means or the time. All the other insecurities, the other practical matters start to impede. But, if I have made on increment of change by this process, then I consider myself successful.

|

Believe You, Me, 1996

Egg tempera on wood panel, 44 x 28 in. |

I’ve traveled a considerable amount and come into contact with architecture, painting, sculpture, music and customs…whatever any group of people or society privately or unconsciously creates as important. Each has a kind of aura or energy of that group’s expression. Never wanting to affect something that belongs to another person or culture, I sort of digest it for awhile; think about it and invariably some vestige, some residue or slight image from that experience comes forward in time.

Over three years ago in Pakistan I was particularly interested in how the interwoven, geometric abstractions in Islamic architecture and their tile work came to symbolize harmony or universal theory above the outer and interior worlds…almost like an endless loop, but very intricate. That was fascinating to me so I wrote about it; a form of digesting. Then, two years later, paintings that seemed to reference the concept started to emerge. It had to become my own philosophy and relationship to it. So, that is a form of inspiration. Roger: Do you have any expectations or hopes for how others view or appreciate your art? |

Andrew: I’m blessed with the opportunity to make something that catalyzes a particular experience that in some very small way, maybe even in a very momentary way, changes no only that person’s life but changes our lives. I don’t have the certainty, the confidence, or the arrogance to think I am in complete control of my message. I think it’s posed more in terms of a question, as a kind of catalyst, something on my mind, some scratch that needs itching. When someone joins in that, I feel it’s more a partnership of experience, if you will a kind of collaboration between maker and viewer. We have been joined, albeit temporarily, in the overall completion of a work, and the greater purpose.

Excerpted from an interview with Roger Breisch & Joe Triolo, May 8, 1997