Selected Interviews

Only Collect: Our Secret Agent Goes Digging for Five Artists’ Hidden Treasures

Mouth to Mouth: The Chicago art scene speaks for itself, Spring/Summer, 2004

- Julie Farstad

|

First, Andrew, how about a statement on your work?

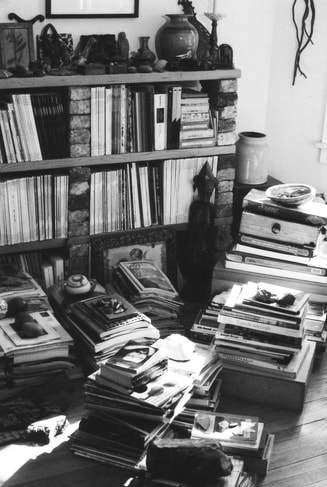

In a sentence? Okay. My art attempts to span the breadth of human experience — somewhere between an awareness of our physical, mortal, and terrestrial selves, and everything spiritual to which we aspire through our academics, religion, philosophies, and writing. Is that encompassing enough? Shelf in the artist’s living room with sculpture and

curios from around the world |

Greater and Lesser Lights series (c-193), 2001.

Collage of hand-painted papers, with Chinese stamp and text, and vintage photograph on museum board, 31.25 x 23.5 in. |

What do you collect?

Ancient coins, American coins and currency, stamps, tintype photographs, 1930’s cigarette cards, vintage postcards and photographs, Islamic prayer-book pages, South Asian textiles, Russian icons, pre-Columbian South American figurines, prehistoric arrowheads and spear points, seashells, rocks, minerals, fossils, 19th-century engravings of plant parts and shells, old-fashioned games that require some kind of pure or direct manual skill, marbles, small boxes and containers, vintage family photos, peculiar texts, artwork, pottery, statues, art books, and natural history references. Then there’s a file I call “Amazing Things,” which are paradoxical and thought-provoking items I’ve clipped from magazines or recorded. My family and friends also send me things, and every year we have a run-off when we rate them as “somewhat amazing,” “particularly amazing,” or “beyond amazing,” and then choose the winner.

Ancient coins, American coins and currency, stamps, tintype photographs, 1930’s cigarette cards, vintage postcards and photographs, Islamic prayer-book pages, South Asian textiles, Russian icons, pre-Columbian South American figurines, prehistoric arrowheads and spear points, seashells, rocks, minerals, fossils, 19th-century engravings of plant parts and shells, old-fashioned games that require some kind of pure or direct manual skill, marbles, small boxes and containers, vintage family photos, peculiar texts, artwork, pottery, statues, art books, and natural history references. Then there’s a file I call “Amazing Things,” which are paradoxical and thought-provoking items I’ve clipped from magazines or recorded. My family and friends also send me things, and every year we have a run-off when we rate them as “somewhat amazing,” “particularly amazing,” or “beyond amazing,” and then choose the winner.

|

Caught by Hand series (c-247), 2002.

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 26 x 20.5 in. |

How long have you been collecting?

Ever since I was a kid. We lived on the East Coast, and I love the ocean. So I would be the one who spent most of any family outing with my arms and legs—and head—in a tidal pool. They would find me in the seaweed, pulling things out and sorting them. Maybe collecting starts with this sensitivity and/or weird ability to spend a long period of time looking at something. Later on, I was a working biologist for three years, so I also have a disposition towards organization. But the impetus to amass or collect or sort is never-ending. Someday, I’ll probably have to move out of town simply to have space to put things. What draws you to these things? Everything has a story attached—it has been discovered, investigated, researched, excavated, or uncovered by me, personally. In some cases, there’s a sentimental attachment—it may have been my grandfather’s, or been given to me by a special person. There are running themes that have to do with natural history, and then artifacts that seem to evidence a very basic humanity that represents physical proximity to our beingness and our connection to the natural. Fundamentally, I think that’s the draw for me. Maybe the sorting, the organization, the categorization, the reframing, and the contextualization are part of that longing for an association or connection to the world. |

|

Many of your collections come from your travels. Do you collect things from where you happen to be, or do you travel to seek out a particular object?

I would say the former. My father was in the Foreign Service, and early in our lives he took us to Europe to live in Switzerland. He also had this sensibility about collecting from his travels. Through various fellowships, exhibitions, and teaching opportunities, I’ve been able to travel to Ecuador three times, and to Pakistan, and I would always tack on a day or two to explore what those places were about—the mechanisms behind their identity. So the collections are very much a consequence of what I’ve been able to access. |

Wall in the artist’s home with Russian icons alongside Rhymes are Games, 1996. Egg tempera on wood panel, 44 x 34 in.

|

|

Seashells and bones collected by the artist

|

What’s the most extreme thing you’ve done to obtain something for your collection?

Once, I was searching for fossils by a river in northern California; they were embedded in a sandstone wall that was dissolving and quickly turning to mud. I decided that to get to some of the better locations, I should rappel off the top of this 80-foot-high cliff using not ropes, but the available roots of a coastal redwood tree. And roots are not as reliable as one might imagine. So I’m hanging by a root while holding a hammer, calling below for people to catch these fossils because I didn’t have a spare hand in which to nest them. Clearly, there was a stupidity element that was completely superseded by my determination to find the most exquisite scallop fossils. That was a little bit crazy…but I was in my 20s. |

|

Do you see any connection between the objects you collect and the artwork you make?

My collections don’t ever physically find their way into the studio—I think it would be a strange kind of mimicry to draw straight from the objects. But the spirit of my most recent works has everything to do with what is gained, and lost, by the event of collecting. What is it that compels us—or me, specifically—to collect and sort, if not to find ourselves in some kind of relationship to our surroundings, and therefore be more stable and secure in that experience? Also the attitude toward collecting in those works is like that of the Renaissance artists; when they added birds and botanicals to their encyclopedias, those elements were always more beautiful in the catalogue than they were in real life—they were somehow idealized. So the very act of collecting or representing almost suggests the loss of the thing in its real state. The artwork—like the way I contemplate the things I own or possess temporarily—becomes a surrogate for something, and the experience I once had with it. |

Reflections Stirred series (c-222), 2002.

Collage of hand-painted papers, with vintage photograph, on museum board, 24.5 x 35 in. |

|

One corner of the artist’s living room

|

Is there a connection between the search for the collectable object and its eventual acquisition, and the process of making a work and its final product? Yes. I once read this story about the sculptor, Constantin Brancusi; whenever a dealer or a museum would take something on loan from his studio, it would create a vacancy in the unconscious arrangement of objects in his sanctuary. So he would make a surrogate of that object — essentially a copy — to take its place, and to keep that experience of his artistic development intact. I’ve never quite overcome the subtle grieving when work leaves the studio. There’s a small impulse to recover these familiar friends that were the art objects. Similarly, with collections, there’s this unconscious arrangement and rearrangement to make the experiences they represent available, and when objects are missing or put away, there’s a psychological experience of disruption. It’s not a materialistic attachment, but a memory issue -- wanting to remember everything I’ve come near in my life, and everything with which I’ve had some kind of intimate experience. That’s what collecting is — it’s the way to find that intimacy again and again.

|