Process

Found Pigments

|

When I was in junior high school in the mid-1970s,

I was given a history class assignment to draft a fictional letter in the voice of a Civil War soldier writing home. I don’t specifically remember the text, but the sentiment was certainly one of love and missing, and directed to his wife whom he hadn’t seen in years. What is very memorable about the piece is the painstaking effort I took to make the physical document feel authentic. In fact, I think I went overboard with staining the paper in black tea and burning its edges to make it physically appear as war-torn as the author’s heart was in words. I was surprised at first, then engrossed in the possibility of capturing time and emotion in a material artifact. I was also taking an art class at the school and making drawings in my spare time, so I imagine it was instinctive to elevate the object aspect in tandem with, if not beyond, the reading of the text itself. The letter was displayed alongside others in a glass case in the main hallway. Since I paid so much attention to the weathering of the letter’s surface, only some words and phrases were immediately legible – descriptions and pleadings I intentionally left undamaged or reworked to come forward in view. In this otherwise straightforward assignment on American history, I was also learning about the evocative power of language, material, and an allusion to time. |

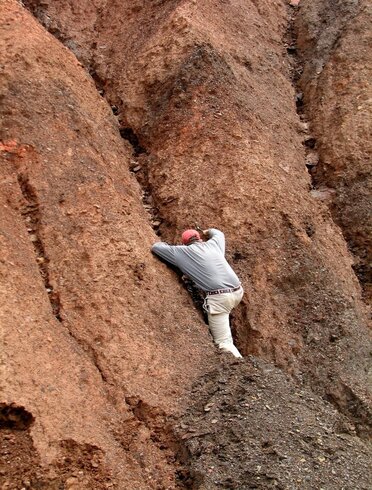

Excavating fossils and pigments on an abandoned 1870s shaft mine "gob" pile in Braceville, Illinois. The red color is due to coal in the spoils spontaneously combusting and smoldering for years, essentially burning the shale which then oxidized in the elements for over a century.

|

|

A tool of the trade when collecting fossils, coal, iron oxides, and ochres in Illinois mines. This rock hammer I purchased when I was 12 and I continued to use it.

|

Evidence of early humans using pigments and paint-making equipment for aesthetic purposes goes back hundreds of thousands of years. It’s understandable that the colors first used would be naturally occurring and readily available. Archaeologists have found iron oxides, ochre yellows, and umbers as ingredients in some of the earliest known cave paintings. Until just a few centuries ago, the range of colors available for art and decoration was restricted by the limits of technology and trade. As a result of scarcity, the more costly or harder-to-obtain pigments took on a special value – perhaps a symbolic one – as they were associated with royalty and religion. Blue and purple, for example, were tied to power and wealth specifically because of their rarity. Ultramarine came from semi-precious lapis lazuli mined in distant Afghanistan, and purple had a most unusual source: the mucous of a living Murex snail. Carmine (an organic pigment derived from a cochineal insect in South and Central America) was discovered by the Spanish and brought back to Europe for use in religious garments. Back in the day, it was the second most valuable export after silver. So pigments – be they of mineral or biological origin – took on status in their use based on the difficulty in obtaining them. Sources and processes were often kept secret so as to maintain their perceived value.

|

|

On a university study abroad program in Italy, I became interested in the Early Renaissance fresco and panel artists of Tuscany. I was fascinated with the luminosity and durability of the finished paintings, as well as the physicality of their techniques. As a lifelong collector and observer of the natural world, I couldn’t dissociate the tactile artifacts and their spiritual content from the basic earthly materials that composed them. Upon returning to California, I took classes and started painting in these traditional media, including using hand-ground watercolor with crystalline gum arabic as the binder. The hands-on vehicle in each process – whether of raw egg, tree gum, or plaster – lent an important physicality to the work and a “second awareness” behind each image that was painted.

It was the first stage in a conceptual separation of ingredients: light versus ground, space from gravity, heaven back to earth. A self-consciousness of the physical became part of the intention in my studio practice going forward. I felt that implied light and perspective – any “references” for that matter – were symbolic of our human aspirations, the timeless, and ethereal. The layered, incised, and gouged elements in relief (say, the sculptural) had everything to do with transience, mortality, and time. |

Collecting pigment in Silverton, Colorado, after the area experienced an environmental disaster in 2015 when an abandoned mine released three million gallons of wastewater into local rivers. The toxic sludge coated everything it came in contact with and dried like paint when exposed to air. Heavy metals wreaked havoc on

the regional ecology. This is an acute case where human interaction with the landscape leaves a monumental destructive trace. (And, yes, I washed my hands thoroughly after this encounter.) |

|

Andrew Young, Five Fish Feeding, 1990.

Egg tempera on wood panel, 35.5 x 27.5 in. Collection of Shirley Worthman, Grosse Pointe, MI |

Egg tempera is a painting medium that mixes dry, powdered pigments with egg whites or yolk and is applied in thin layers or “skins” which allow light to penetrate and illuminate the surface. Tempera is also leathery and malleable for a short time after application; just enough so to permit unorthodox, nontraditional manipulations that make the object look decayed from time. And, as “time” became a component of my work by virtue of the artifact appearing to have had a previous life, so did I start incorporating found elements: literally bringing in other worlds and histories that each additional piece represented. Collage/assemblage aesthetics supplanted the purer egg tempera approach. Were it not the case where I introduced an actual foreign object to the recipe, I would set out to carefully hand-make one that looked that way.

|

|

Early collage artists such as Kurt Schwitters and Joseph Cornell were influential to me, as was the American “neo-Dadaist” Robert Rauschenberg. European proto-Arte Povera artists, Antoni Tàpies, and Alberto Burri were especially interesting for the immediacy they brought to their work through unconventional materials and gestures. A quote from the 1960 Venice Biennale catalogue interprets Alberto Burri this way: “For Burri, we must speak for an overturned Trompe-l’oeil because it is no more painting to simulate reality, but it is reality to simulate painting.” In the 1950s, when Burri started to make art with common jute fabric sacks distributed by the Marshall Plan in post-War Europe, color in the picture plane receded and surface coincided with the material he employed. There was no longer any separation between the two. Painting and matter were now equal.

|

Alberto Burri, (Italian, 1915-1995).

Sacchi (Sacks), jute fabric on canvas, circa 1952. |

|

Drying silty mud and seedlings, Braceville, Illinois.

Coal from an abandoned strip mine, Wilmington, IL.

|

For years, my egg tempera paintings were accompanied by a side, almost secretive process of watercolor on museum board. I believe it was in the latter I worked out the “spirit” underneath – or within, or beyond – the design of the labor-intensive tempera panels. I used some of the same mineral pigments as the temperas but also started introducing color and material from other places. I suppose as the alternative, clandestine practice of working on paper brought more immediacy to my hand and thought process, so did searching for other material sources expand my “palette” outside the studio and connect me there. The small planes of paper carried all of the hands-on attention as the wood panels (the scuffing, the folding, the staining, painting, and erasing), and when it was time to go public with the pieces,

I figured a way to glue them more or less permanently into a collage. Formalizing this process expanded my professional practice into a new medium, but also denied me the privacy of the original gesture of making things I would more likely keep folded in my pocket than framed on a wall. |

|

The subject matter in my work has always had something to do with our relationship to the natural world. Nature itself is breathtaking and mysterious, and deserves to be glorified, but with my art I’ve become much more interested in the distance between us and our surroundings, and the way we interpret or manipulate nature to conform to what we think of as “natural.” If the application of raw mineral pigments in my early egg temperas was to revisit and somewhat abuse the techniques of Renaissance Masters for the purpose of showing a human emotional space between higher spiritual aspirations and our earthly mortal selves, then the underpinning of the collages would be a striving to address the language of natural history: the way we classify nature and what is says about us. The more I thought about the landscape, the more elusive nature seemed to me. Along with a more singular focus on collage-then-mixed media studio work came a coincident practice of collecting fossils, stones, ores, and natural pigments from field trips all over the state and country. Just as the material ingredient in Antonio Burri’s 1950s work rose in presence and meaning equivalent to anything pictorial, I was literally bringing nature as I found her into my practice and, in turn, the notion of “place” became a new arena for content.

|

An abandoned 1870s shaft mine spoil pile, Braceville, Illinois.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917).

Russet Landscape, 1890, monotype print in oil on paper. Degas is famous for his ballerina drawings and paintings, but I find his approach to landscape most avante-garde. The gestures are refined, the imagery abstract, and the material characteristics in the artwork come completely forward. |

|

Robert Smithson (American, 1938 - 1973).

Spiral Jetty, 1970. basalt rock and earth, 1500 ft. long x 15-ft. wide. The artist wrote that he chose the site because of its proximity to remnants of a derelict oil jetty. In years following, oil and gas extraction has threatened the area's ecology. |

When I was a college student in California, I had the privilege of studying the history of sculpture with Peter Selz, former curator at the Museum of Modern Art (1958-1965) and founding director of the Berkeley Art Museum. I was majoring in biology at the time, but starting out with some measure of seriousness in art history and studio practice. One particular movement in 20th century art grabbed my attention then – nearly 35 years ago – that keeps circling back into my process for what seem today like obvious reasons. The Land Art movement of the 1960s and 70s was concurrent with a growing ecological concern in America and Britain. The work from it utilized material from the earth and was usually site-specific in places far away from urban centers. In a context outside of a studio, gallery, or museum, the scale of any artist’s gesture is entirely altered. If the relationship of humans to Earth, or to the cosmos, or to geologic time is central, creating art as an “action” in the landscape is foremost at expressing this.

|

|

Land art derives from nature and is almost invariably temporary. British artist, Richard Long, interests me for the subtlety of his marks on the ground, paring down the making of his work to mapping or tracing his movement through the landscape, and essentially reducing art to linear motion and the ephemeral. By contrast, Robert Smithson moved quite a bit of earth to create Spiral Jetty (1970), a site-specific sculpture on the Great Salt Lake in northern Utah. It utilizes local volcanic rocks and mud in a winding geometry, and periodically disappears from view when lake levels rise. David Nash began a project in 1978 entitled Wooden Boulder where a large sphere of wood, carved by the artist and left out in the Welsh countryside, has over many years made its way down streams and valleys to rest in a river estuary. It was last seen in 2013. The project conforms to the idea that something which grew out of the land will eventually return to it.

|

David Nash (British, b. 1945)

Wooden Boulder, 1978, hand-hewn oak wood, roughly 3-feet in diameter. The artist uses coarse implements - axes, chain saws, and fire - to make sculpture in response to nature. |

|

A coiled cephalopod in 400-million-year-old Niagara limestone, Thornton, Illinois. The bitumen in its chambers was harvested for pigment.

A Wilmington, Illinois, seed fern fossil (300 million

years old) as a fugitive carbon impression on shale. |

Along with my passion for collecting and writing about fossils (as well as volunteering in museums to assist in identifying and cataloging them), I have brought materials from various fossil localities into my artwork because of the specificity of the source. Whereas, I once made objects “look” old by physically manipulating their surfaces, now oxidation, sedimentation, and other natural processes do the work in their own way and I go along for the ride. Also, a new scale for time arrives when the age of fossiliferous strata is known and geologic relationships are introduced. In a recent exhibition entitled All This Land, I used found, hand-processed pigments from regional Carboniferous coal deposits, freshwater oyster shells, prehistoric marine sediments, fossil concretion ochres and iron oxides, and bitumen from Silurian Period reef organisms. The harvesting of these natural pigments is time consuming, but I recognize the action as part of a larger process. It connects me and hopefully the artwork to a place, and the method and repetition involved in cleaning and preparing the minerals for paint is ritual.

|

|

I’ve been making pigment pieces I call Horizons for their simple landscape-like features, but they really represent a convergence of two disparate sources of material: different locations geographically, geologically, culturally, and politically. In them, I see what is circular in our world. I collect and render the sedimentary stones into finer bits that can be suspended in a liquid binder as paint. Then, the slurry is laid down without arresting or hiding its characteristic weight and density. It is slowly and patiently layered, as if with ancient memory, the same way the grains once fell to an ocean floor. I have reconstituted these silts in suspension, and then coaxed them to rest once again in form. It is the perfect evolution of my art and - as with Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking (1967) - an allegory of life itself: materiality through action, place, and repetition. We are but modest vessels in a larger progression, happening naturally, and for all time.

|

Richard Long (British, b. 1945)

A Line Made by Walking, 1967, black & white photo documentation of a straight path walked until a line in the field was visible. |

© The above artworks may be protected by copyright. They are posted on this site in accordance with

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.