Selected Catalog Essays

Transcendent Nature: Sources of Inquiry in the Art of Andrew Young

I Space, University of Illinois, Chicago 2001

- Julie Sasse, Chief Curator, Tucson Museum of Art

|

Let us now suppose that in the mind of each man there is an aviary of all sorts of birds—some flocking apart from the rest, others in small groups, others solitary, flying anywhere and everywhere. . . . We may suppose that the birds are kinds of knowledge, and that when we were children, this receptacle was empty; whenever a man has gotten and detained in the enclosure a kind of knowledge, he may be said to have learned or discovered the thing which is the subject of the knowledge: and this is to know. - Plato

|

|

Transcendent Nature

Philosophers, writers and artists throughout the ages have sought transcendent refuge and spiritual enlightenment through scientific and creative investigations of nature. In Plato’s Symposium, among several of his early Dialogues of Search, he reinforces the basic metaphysic of his Theory of Forms, holding that total reality includes not only the world of our senses, but another realm beyond space and time. This other realm contains the unchanging and ultimately significant principles in whose perspective man must live his life if he is to live it well.1 Plato articulates in his dialogues the power of love and its presence in nature, from animals and plants to the highest vision of truth. Centuries later, the artist and educator John Ruskin echoed Plato’s search for enlightenment and understanding through the wonders of creation, natural forms and processes, and the achievements of humanity.2 For Ruskin, the inquiry into nature must have a higher purpose than empirical science; the study of plants, animals, and geology is a means to discover the poetry of life and the beauties of the world. The ongoing quests for knowing—through nature, beauty, and art—is the search for what is greater than ourselves and ultimately a way to find common bonds with all that is around us—a search for love. Andrew Young follows that familiar path, continuing to search for what has eluded humankind throughout time. In doing so, he creates intimate, poetic, and beautiful works of art that are unique and timeless. |

Collages series (c-78), 1999

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 16.5 x 14 in. |

|

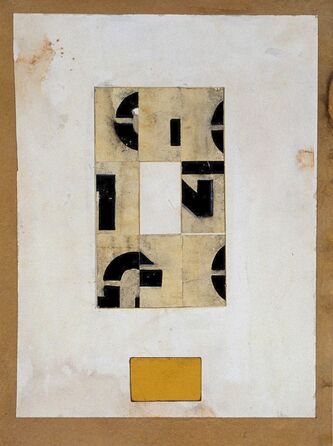

Collages series (c-79), 1999

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 18 x 13 in. |

Like Ruskin, Andrew Young’s interest in the transcendental nature of art and science began with a formal and familial background that included both areas of intellectual education. Long interested in art (his mother was a painter and stage actress), he made collages and paintings on his own throughout his childhood and adolescence. But love of natural history was equal to his passion for art, so in 1981 Young entered the University of California at Berkeley as a biology major, and worked for years in microbiology and zoology laboratories. The creative urge, however, never left him. At school, Young kept a drawer filled with neatly arranged art supplies, just as his collections of shells, stones, and other objects from nature retained a fascination for him. Knowing of his parallel and ongoing interest in art, his stepmother, who was a sculptor in her own right, encouraged him to apply for a Rotary International Scholarship in 1983 to study in Siena, Italy. Through this scholarship he was able to focus on language and art history, temporarily breaking from his studies in science to investigate the humanities in a region alive with historic inspiration and romantic associations.

Young’s experience in Italy caused a shift in his thinking. Inspired by Renaissance and Sienese painters and techniques of the 15th century, he returned to the United States determined to learn more about art and experiment with painting. Although his impulse to create art intensified, he was uncertain that art could replace his professional ambition of becoming a scientist, so he continued his biology studies at Berkeley for a few more years. Intrigued by the luminous qualities in the paintings he had seen in Italy, however, in 1985 he found a teacher to instruct him in the time-honored techniques of egg tempera and fresco. |

When his curiosity about art grew to a passion, he focused on art history, philosophy, the classics, and studio art. Armed with a developing understanding of the humanities and a solid technical foundation, he embarked on a series of paintings that thrust him into a completely different realm than the sciences. He took with him on his new journey an intense wonder and love of nature, now manifested in art. Young left the scientific laboratory for the artistic one—like a pensive alchemist working on the floor of his studio, grinding pigments and mixing in the yolks of eggs—and embarked on a lifelong search for the essence of life through art.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Berkeley in 1987, Young focused on studio art. He moved to the Midwest to refine his technique and in 1989 completed a Master of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Sensual notations of flowers, and occasionally birds, among washes and splashes of umber, gold and sienna, were among the first egg tempera works he showed publicly in the early 1990s. These abstractions were held to the composition by niches and frameworks of geometric lines, architectural details and subtle curvilinear elements.3 Versed in the traditions of the Sienese painters, he delved into stylistic elements of Symbolism and Art Nouveau, while keeping firmly on a contemporary path. Intimate in nature—with their warm, crackled patinas (an allusion to the decline of the physical body and ultimate mortality)—his work was imbued with a timeless preciousness by the selective merging of palette, technique and stylistic overtone. Evoking a sense of indefinable nostalgia, melancholy and longing, these works created a pull to emotional realms while holding the viewer to reality through the referential grounding of the elements of nature. Writer Allison Gamble noted that Young, by the careful orchestration of image and spatially ambiguous abstraction, “indexes the depth of our intimacy with the purely painterly passage against the shifting stresses on intent and interpretation over history. And he has done so by carefully constructing an axis of airless artifice between viewer and pictorial surface, a space of anxious possibility.”4 The compelling nature of these paintings produces a sense of the sublime by merging the rational with a wild abandon.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Berkeley in 1987, Young focused on studio art. He moved to the Midwest to refine his technique and in 1989 completed a Master of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Sensual notations of flowers, and occasionally birds, among washes and splashes of umber, gold and sienna, were among the first egg tempera works he showed publicly in the early 1990s. These abstractions were held to the composition by niches and frameworks of geometric lines, architectural details and subtle curvilinear elements.3 Versed in the traditions of the Sienese painters, he delved into stylistic elements of Symbolism and Art Nouveau, while keeping firmly on a contemporary path. Intimate in nature—with their warm, crackled patinas (an allusion to the decline of the physical body and ultimate mortality)—his work was imbued with a timeless preciousness by the selective merging of palette, technique and stylistic overtone. Evoking a sense of indefinable nostalgia, melancholy and longing, these works created a pull to emotional realms while holding the viewer to reality through the referential grounding of the elements of nature. Writer Allison Gamble noted that Young, by the careful orchestration of image and spatially ambiguous abstraction, “indexes the depth of our intimacy with the purely painterly passage against the shifting stresses on intent and interpretation over history. And he has done so by carefully constructing an axis of airless artifice between viewer and pictorial surface, a space of anxious possibility.”4 The compelling nature of these paintings produces a sense of the sublime by merging the rational with a wild abandon.

|

Young continued to explore the qualities of ideal beauty and transcendence through egg tempera paintings and watercolors throughout the 1990s. As the images unfolded, new sources of visual engagement emerged in his art that expanded the associations with art history, culture, and spirituality. In 1993 he traveled to Lahore, Pakistan, on a fellowship to teach at the National College of Arts, where he was exposed to Islamic tile work from the Mughal period of the late 1500s and early 1600s, and the spiritual, utopian and metaphysical ideals that enrich such abstractions. The influences were not immediate, but within a few years his flowers, always created from his imagination, shared ground with the rich complexities of non-referential, geometric ordering.

The clash between East and West in Young’s resulting work acts like the passion of opposites. Young’s earlier emphatic marks had the loose quality of the floral tendrils of Art Nouveau, which in kind had borrowed from Islamic “arabesque,” the typical expression of the Islamic perception of the world. Found in the floral patterns covering the walls of palaces, in embroideries and carpets, and in the design of precious manuscripts, the naturalistic sources of “arabesque” also refer to the geometric ornamentation found in Islamic buildings.5 The geometric patterning in the crystalline character of this art form became a recurring motif in Young’s work. Often replacing the architectural “framing” devices of niche references, the geometric patterning opened new doors of artistic expression for him. Highly structured and richly colored, these patterns further linked his work to concepts of spirituality. Since his abstracted flowers and birds act as surrogates for human presence, Young’s use of metaphoric and symbolic associations complement the Islamic aim to depict things in abstraction—to reach a deeper meaning rather than to replicate the world as it appears to the eye. |

Collages series (c-51), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 18 x 14 in. |

The geometric “arabesque” has been an influencing factor in art throughout history. In the late 1800s, art historian Alois Riegl supported the use of geometric abstraction, inspired by Islamic art, as a way for the eye and the mind to be transcended. He postulated this idea:

|

Therefore the crystalline motif is for human art production, which has to do exclusively with inorganic matter (including originally organic substances that have been robbed of growth and are therefore lifeless like wood and ivory), the only adequate and justifiable motif, because, from the beginning, it is simply the natural one. Only in inorganic creation does man appear fully nature’s equal.6

|

Of course, artists have long borrowed decorative details from Islamic art, but the power of spiritual associations did not become clear until modern times. Philipp Otto Runge, Maurice Denis, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Gustav Klimt, Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Henri Matisse and Jackson Pollock, among countless others, found relevance in patterning, abstraction and geometry as a way of seeing. In a continuance of this tendency, Young found not only a fascination with the enlightening capabilities of geometric structures, but successfully merged it with organic representation. Young’s sense of ordering—the layering and juxtaposition of fluid, organic shape with the tight, grid-like lines of geometry—holds his conglomerate compositions together. In a sense it mirrors the pull of man from his organic, real state to a higher consciousness—the coexistence of both states of being emblematic of how we move through life.

|

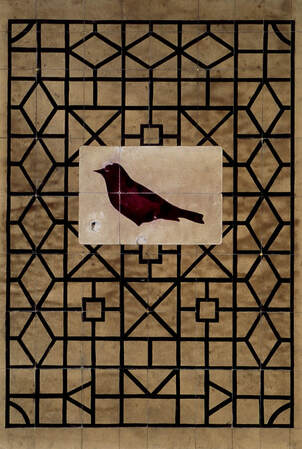

Collages series (c-49), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 21.5 x 15 in. |

A pivotal shift in Young’s work came about in early 1998 when he suddenly found himself overextended with demands for his paintings. A year after participating in the V Cuenca Bienal of Painting, the bulk of his work was at a private gallery in Ecuador, held there due to political upheaval. Faced with deadlines, Young drew on some of the resources he had collected on his travels. Young had made small drawings on paper, primarily bird shapes, which he carefully folded, bifurcating the images, and stuffed them in his painter’s jumpsuit. Created in a state of self-reflection, the small pieces of paper acted as an abstracted, visual diary. The singular bird in the middle of each, that he called a “messenger,” is a reminder of the self, that the artist is present in all the work.7 Young didn’t make these intimate paintings for sale; they were simple reminders of home—a sense of place that represented safety and grounding at a time of personal transition. Thus it was natural to return to the growing mass of papers that could unlock the door to his longing. The result of that emotional baring of his soul was to become the basis for a new direction—the collages that now hallmark Young’s current work.

Returning to the intuitive and introspective quality of layering and ordering individually painted papers, Young reclaimed a sense of privacy and renewed a sense of spontaneity in his work. Still, his need for compositional ordering, his method of working on a flat surface (much like Mondrian), and his unabashed yet reverential borrowing from art history’s stylistic elements, continued. The earlier expressive abstractions, however, receded and a stronger presence of identifiable elements, stylized to avoid a tendency for specific representation, emerged with a heightened sense of lyricism. Considering himself an abstract painter first and foremost, he continued to use geometry as an anchoring force. Before, geometry and architecture were framing devices (niches as enclosing references); now a newer sense of openness is apparent. No longer possessed with a feeling of dark confinement, the new paintings fill the picture plane and geometry defines a liberating window. |

|

While elements of geometry and abstraction were ever-present in Young’s work, such as in c-78 and c-79, at times Islamic references reappeared with an ironic twist. Not wasting an opportunity to comment on cultural perceptions of beauty, in c-51 he reproduced a linoleum floor pattern inspired by Islamic tile work that he found in his apartment. Reminded of the grandeur of such designs in their original setting, Young appropriated the highly geometric interlocking shapes now assigned to low art as a mass-produced product, “reclaiming” the patterns and elevated them back to their former elegance and spiritual meaning.

Another such emblematic rescue can be seen in c-49 in which a black, linear pattern in an ornamental grid overlaying a tan background frames a deep red and black solitary bird. Once again emulating Islamic crystalline arabesque, the inspiration actually came to the artist from a Victorian cast iron grill for a heating duct in his Vermont home. Referencing a ceramic lattice window treatment that Young had seen in Pakistan, he redrew the grate pattern from memory, expanded on the theme and used it as a framing device to encage the bird, a reference perhaps to the women of the harem treated in similar fashion in times long past. But spatial concerns are much more important than social implications in this work. Young employs this flattening effect as a formal device and a clue to the reading of the painting. The picture plane condenses, like the dense gestures of the calligraphy on the pages of the Koran. Once again the design elements of his delicately collaged paintings serve to send broader messages through thoughtful melding of abstraction and representation. |

Collages series (c-81), 1999

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 14 x 10.25 in. |

|

Collages series (c-50), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 15.25 x 11 in. |

A sense of harmony has overtaken the tug of war between the defining of space through line and the urgency of the sense of chaos (or what the artist playfully refers to as the “misbehaving” of the composition) in the recesses of dark space and splashes of random paint of his earlier paintings. Young articulates the control of his compositions, as in c-81 and c-50, and their various elements as an emulation of humankind’s intrinsic or natural tendency to try to make sense of the world around us, to control it, to keep it within the realm of the known. But it is a liberating, not an oppressive ordering. Like an English garden, the carefully composed works have a sense of enlightenment, more hopeful and free of existential angst than his earlier egg tempera paintings. It is as if through his art Young has decided that answers can be found and that spiritual transcendence can be achieved.

Elements of order and classification are apparent in Young’s works on paper, particularly influences derived from the works of John F. Peto (1854-1907), whom the artist admires. Peto’s early rack paintings, which in turn are indebted to seventeenth century Dutch and Flemish paintings, serve as clear inspiration for Young’s collages. Peto created vertical compositions with objects suspended in a tape grid and mounted on a “wooden” support in trompe l’oeil still life paintings of cards, letters, and other written and printed materials.8 Young does not attempt to emulate the illusionist qualities and density of Peto’s painted surface in his work. However, by creating his collage elements to look like bits of found and collected letters, drawings, postcards, and botanical documentation, he leads the viewer to believe that his assembly of time-worn scraps of nature observed and life experienced are from sources outside the studio. Turning to the contemplative, autobiographical nature of their work, Peto and Young address mutability and the passage of time through the worn effects of the various elements within the composition and selection of the items they illustrate. |

In Young’s case, the autobiography becomes two-fold. The collages express his passion for nature, science, history, and distant places. Yet they also serve as an emotional mapping of his life through image and order, all of which are underscored by a sense of time and a longing for something unknown or unfelt. Young expresses his curiosity about the intersection between art and science in c-40, pulling from the pages of his past and taking a cue from Victorian naturalists. In this collage, large, graphic numbers are cut up and reordered, framing nothing. Under this rectangle of abstraction, a yellowed specimen label identifies emptiness. As Young explains, “As a biologist, all of our descriptions, formulas, and equations, in the form of genetic codes, identity codes and other numerical notations, are set up to describe the essence of matter. In this piece I cut up such classifications and scramble them, but the sense of codification is still there.”9 Young’s observation that the essence of nature is always there, whether or not it is subjected to taxonomy, is a reminder of his attempt to understand larger issues of existence through his artistic language of images and symbols.

|

Conceptually and visually, Young’s collages relate to the work of Surrealist Joseph Cornell (1903-1972). Cornell took the idea of the systematically arranged, trompe l’oeil paintings by Peto to a three-dimensional format. Beginning at first to create collages, Cornell discovered the box as a way to express his interest in Victorian mementos and fantasies of time and distant place with precision and poetic control. Cornell’s arrangement of objects in grids became altars to memory and lost childhood, a sense of high nostalgia to which Young relates. Additionally, Cornell explored concepts relating to the forces of nature, in particular referencing his interest in astronomy.10 The overriding tone of melancholy and longing in Cornell’s boxes, combined with the sense of intimacy they evoke through their small size and the selection of objects, touches Young’s own desire to express sensations of solitude, sadness and desire, rather than the formal emulation of the visual aspects of the subject matter.11

Young’s passionate interest in art history and those artists who have achieved elements of what he seeks formally and emotively, helps to explain the rich fabric that makes up his art. Since structure, order, and achieving a higher state of understanding are paramount in Young’s work, it seems natural that he would have an affinity for the works of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). Mondrian, a Theosophist whose early art was rooted in Romanticism, denounced ornamentation and abhorred repetition and individuality. Young embraces Mondrian’s formal ordering of space in grids, the distillation of the world around him into the essence of experience, and the transcendent qualities of painting. Mondrian eloquently discussed his theoretical principles in 1937 when he said: |

Collages series (c-40), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 14 x 11 in. |

|

Although art is fundamentally everywhere and always the same, nevertheless two main human inclinations, diametrically opposed to each other, appear in its many and varied expressions. One aims at the direct creation of universal beauty, and the other at the aesthetic expression of oneself, in other words, of that which one thinks and experiences. The first aims at representing reality objectively, the second subjectively. Nevertheless, both the two opposing elements (universal-individual) are indispensable if the work is to rouse emotion.12

|

Young strives for this duality in his work. In Young’s painting c-36, a composition of geometric circles and curves, inspired by Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979), overlays a geometric arrangement of lines and squares in muted tones. Like colorful game boards with endless possibilities of configuration, the work autobiographically marks what Young describes as a “forecast of the day.” The concentric circles, almost target-like conspicuously replace flora or fauna, standing in as figurative surrogates. The melding of representation with abstraction in c-52 also exemplifies Young’s compositional dexterity. In this work the geometry loosens and flora divide the picture plane into four distinct areas; his poetic achievements toward beauty and self-discovery are reinforced.

|

Collages series (c-36), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 14.5 x 10.25 in. |

While control and systematic order seem to prevail in Young’s paper works, their strength still relies on the emotive qualities that the works contain. In an almost opposite approach, but indicative of how Young embraces a wide range of artistic sources, he has looked to Emil Nolde (1867-1956) and the emotional impact of his landscapes and figurative paintings. Nolde, and other German Expressionists of his time, insisted that art address the artists’ feelings, for the most part as a reaction to World War I which was raging at the time, but also for the emotional impact that such feelings would create in the work. The spiritual bond to primal states and the demonic qualities of “primitive” art and religion influenced Nolde, who had traveled to such far off places as China, Japan, Russia and Polynesia. Affected by states of despair and inner tension, characteristic of other German Expressionists who chose to manifest them in their work, Nolde turned from the angst and embraced ideas of a mystique of the soil, of invisible powers within nature.13

Nolde’s use of color elicited essential, archetypal sources of existence and feeling. What attracts Young to Nolde’s paintings is his random, wild expressiveness, devoid of pictorial refinement, that upon closer inspection solidifies into a recognizable composition. Young responds more directly to the physicality with which Nolde produced his etchings and the importance he placed on process. Using gravel and sand to activate his surfaces, Nolde attacked his woodcuts and etchings with reckless abandon, producing intensely emotional graphics that had an even greater immediacy and spatial economy than his paintings. Young’s investigation of Nolde’s emotional intensity counterbalances his interest in Mondrian’s spiritual quest through control and serves to inform his own work on many levels. |

|

The tightly defined areas of color in Amish quilts have also made their way into Young’s realm of artistic inquiry, resulting in more immediate associations with his collages. The Amish, who first created their quilts in the late 1800s, avoided the frills and embellishments of Victorian patterns in favor of the more austere juxtaposition of simple rectangular shapes. Designed on a grid, the quilts were offset by one odd-color thread or patch, a humble denotation of their acknowledgement that only God can be perfect. The Amish quilt makers, working within tight boundaries by setting strict compositional restrictions, created myriad combinations and inventive possibilities. Young also works within a familiar framework, keeping the vocabulary of his images and arrangements within a formula that results in untold imaginative compositions.

Just as the Amish created certain confines from which to create, so did Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), who for a time in the late 1920s focused on the compositional variations found in one basic still life that he set up in his studio. At first interested in the strict geometry of his paintings, he abandoned such pursuits in favor of Cézanne’s looser arrangements. Slowly reducing the number of elements in his paintings, he even went so far as to paint over the actual remaining few bottles that he used to set up the still lifes. This put even more restraints on what he saw, but allowed Morandi to concentrate on the simple forms without distraction by color or reflection. What emerged from these works were subtle tonalities and wonderful possibilities, and the variations on theme abounded. As Joan Lukach has observed, “Morandi’s art presents us with a vision of calm, relaxed awareness. But it also confronts us with the thought that such consciousness comes about only through the discipline of unflagging concentration such as the paintings record."14 Young finds comfort in such boundaries and parameters. Retracing the borders of the various papers in his collages reaffirms the distinction of object and subject, a mapping of the form that makes it part of himself by the act of linear definition. |

Collages series (c-52), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 14.5 x 10.25 in. |

|

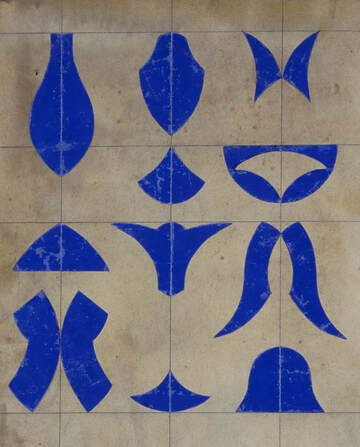

Collages series (c-44), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 14 x 12 in. |

One of the more unusual compositions within Young’s oeuvre, c-44, once again reveals the melding of past and present, formal concerns with emotive ones, and science with art. In this simple, poetically charming piece, a flat background in the coloration of tea stains—reminiscent of the tracing paper used by dressmakers—holds the composition with a grid of straight, slender lines. As if the whole piece has been folded and unfolded, the lines of demarcation divide royal blue, stylized plant forms in bilateral symmetry. Like the formal elegance of Japanese family crests, these simplified shapes are elevated to a higher state of meaning and reverence by their reduction to basic form and purposeful placement. In thoughtful reflection, Young explains the deeper significance of this collage, “In biological specimens, all insect legs are placed upward and incised lines are laid out on a grid. This is done to make sense of them, but plants and insects are never found in such ordered patterns in nature. In an attempt to understand things, we try to order them.”15

Therein lies the dichotomy in Young’s quest, the search for a lost sensibility through identification and ordering, and the realization that by trying to define nature (and thus ourselves) we, as sculptor Henry Moore explains, “defy our ability to understand it.” What attracts us to Young’s art is its visual attempt to seek universal answers and provide a mirror to see ourselves. We connect emotionally to his work because we have the same struggle as we endeavor to understand the world around us. Young expresses this journey as the “spiritual in relation to the terrestrial, and the longing, through classification, to understand our place in the heavens."16 Though humankind may never find the answers, the beautiful inquiries in the art of Andrew Young make the effort all the richer. |

- Julie Sasse, Chief Curator and Curator of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Tucson Museum of Art

Contemporary Art, Tucson Museum of Art

|

1 Whitney J. Oates, Preface to Plato, Lysis, or Friendship the Symposium Phaedrus (Mount Vernon, NY: The Press of A. Colish, 1968), viii.

2 Harriet Whelchel, ed., John Ruskin and the Victorian Eye (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1993), 10. 3 It is interesting to note Young’s fascination with James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), particularly his revolutionary use of abstraction in his melancholic nocturnal scenes of the late 1870s. Whistler, calling the wash of abstraction over his deep night scenes “sauce,” defied the conventions of the time in an attempt to find harmony in the arrangement of forms and colors. His abstractions enraged John Ruskin, who believed the works to be unfinished insults. For more on Whistler’s nocturnal paintings, see Denys Sutton, Nocturne: The Art of James McNeill Whistler (New York: J.B. Lippincott,1964). 4 Allison Gamble, Bilder über dem Wasser, exhibition catalogue, (Bonn: USIA, 1991), 5. 5 Annemarie Schimmel, “The Arabesque and the Islamic View of the World,” in Markus Brüderlin, ed., Ornament and Abstraction: The Dialogue between non-Western, Modern and Contemporary Art (Basel: Foundation Beyeler, 2001). 6 Ibid., 91. The basic premise of Riegl’s argument is that we understand art as initially transforming nature and then as transforming itself from within, out of purposes which are strictly artistic. His notion of style is about the transformation of motifs. See Michael Podro, The Critical Historians of Art (London: Yale University Press, 1982), 71. 7 Birds have been present in Young’s work since the late 1980s, but in limited numbers, usually in the form of one small bird painting within an exhibition that served as a portrait of the artist. Such portraiture was not an egotistic marking of his place in his art, but a reflection on the concept of testament, and the concept of witnessing that which we believe to be consciousness or presence within our environment or reality. The birds became broader metaphors for this concept in the collages that developed. Andrew Young, telephone conversation with the author, 21 July, 2001. 8 While Peto’s early rack paintings were more formalistic and commission-based, his later works became more autobiographical. See Doreen Bolger, “The Early Rack Paintings of John F. Peto: ‘Beneath the Nose of the World’,” in Anne W. Lowenthall, ed., The Object as Subject: Studies in the Interpretation of Still Life (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996), 59. 9 Andrew Young, telephone conversation with the author, 21 July 2001. 10 Diane Waldman, Joseph Cornell (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1977), 28. 11 Another artist, German Dadaist Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), who Young references in this aspect, made carefully organized pastiches of found papers. To Young, Schwitters’ assemblages, “come together, but are not wholly static—they have an interesting lack of cooperation.” Whereas Schwitters looked to his found materials to make them into art, Young prefers to hand make his papers to avoid the seduction of the material. What they share in common is systematic arrangements to create a dynamic whole. For more on Kurt Schwitters, see Manfred Bodin, Kurt Schwitters (Hannover: Sprengel Museum, 1996). 12 Piet Mondrian, “Plastic Art and Pure Plastic Art,” in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, eds., Art in Theory 1900-1990 (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1993), 368. For more on the spiritual motivations and qualities in Mondrian’s paintings see Edward Weisberger, ed.,The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1986). 13 William S. Bradley, Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1986), 7. 14 Joan M. Lukach, “Giorgio Morandi, 20th Century Modern,” in Giorgio Morandi (Des Moines, Iowa: Des MoinesArt Center, 1981), 45. 15 Andrew Young, telephone conversation with the author, 22 July 2001. 16 Andrew Young, artist’s statement, 2000. |

Full-color, printed exhibition catalogs are available with the above essay. Please contact the artist to inquire.