Selected Catalog Essays

All Senses: The Art of Andrew Young

Oakton Community College, Koehnline Museum of Art 2005

- Britt Salvesen, Curator

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson.

|

All Senses: The Art of Andrew Young

Out His Window The limestone rocks at Schoolhouse Beach, on Washington Island, Wisconsin, are smooth and perfectly shaped. Having no sharp edges, they invite touch. These small spheres, disks, and bricks are as finely crafted as sculptures by Brancusi, but they are formed by natural means. Boyer’s Bluff, on the island’s northwest tip, is part of the Niagara escarpment, shaped millions of years ago by subterranean and glacial forces and now battered by wind and water. Periodically, limestone boulders fall away from the bluff and tumble to the shore below. The large chunks, swept into the water, gradually break into pieces and begin to move southward. This process, known as littoral drift, is explained in vigorous terms on an information panel: “Along the shore, below the heaving waves, the rocks work their way, each stone polishing the other for centuries before coming to rest on [the beach]…. Each is a one-of-a-kind phenomenon to be respected.”1 |

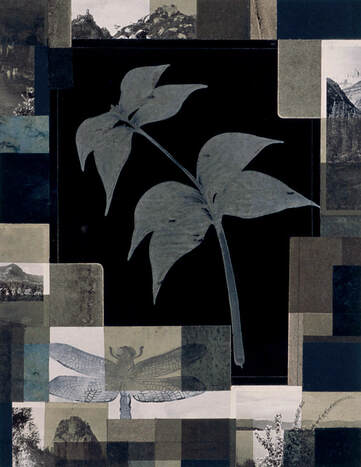

Leaves and Lanterns series (c-300), 2005

Collage of hand-painted papers, and vintage Photographs, on museum board, 15 x 11.75 in |

|

Pottery sherds and minerals collected by the artist

|

Andrew Young spent the summers of his teenage years camping with his family in the Washington Island woods, near Schoolhouse Beach. He has skipped those stones across the water’s surface, stacked them to make towers, felt their warmth or coolness against his skin. The scientific account of their formation is, for him, intrinsic to their allure. From early on, Young has been an observant participant in the natural world. He was the boy who perched for hours at the edge of a tide pool, who turned away from the television to watch birds through the window, who pored over illustrated books on sea and pond life. Schoolhouse Beach is a harbor for him in both senses of the word: a site that offers safety and shelter but at the same time acknowledges the power of water and wind; a place that fosters private mediation on ideas and emotions. |

|

Substantial fines discourage the taking of stones from the beach, and this proscription leads to reflection on the human urge to extract objects from their natural settings. Collecting—as a pursuit and an idea—has been a lifelong interest of Young’s, arising from some combination of instinct and intention. He engages in all aspects of compilation: finding and selecting objects, sorting them into categories, storing them in containers and drawers, displaying them on shelves, learning about their history, examining them in relation to one another, making sketches of them, considering the implications of their displacement. With a hint of affinity, Young describes the species of snails and birds that seek certain kinds of objects and painstakingly affix them to their dwellings. An expressive as well as analytical activity, collecting is also a way to connect with the world. Speaking with an interviewer on the subject of artists’ “hidden treasures” in 2004, Young selectively inventoried his accumulations of coins, pottery sherds, ferrotypes, stamps, Islamic prayer-book pages, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russian icons, pre-Columbian figurines, prehistoric arrowheads, seashells, rocks, minerals, fossils, marbles, peculiar texts, and vintage postcards.2

|

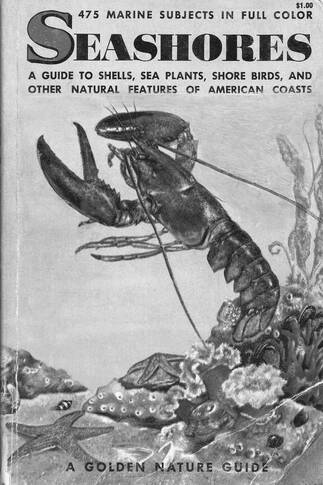

Field guide owned by the artist as a boy

|

|

Given his youthful inclination toward natural history, it is not surprising to learn that Young studied biology at the University of California–Berkeley. Given his equally strong desire for identification with nature, it is likewise plausible that he would go on to study painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Today, these two paths are considered by many to be in opposition—science versus art, object versus subject, fact versus feeling—but Young sought to integrate his concerns, aptitudes, and ambitions. The naturalism that animates his process and paintings, therefore, has historical antecedents and contemporary implications.

|

|

Animals on Show, 1988

Egg tempera on wood panel, 20 x 16 in. |

Young approaches the world with abiding curiosity, reminding us that the word connoted “scientific or artistic interest” in the seventeenth century; it also described a quality of “careful or elaborate workmanship.” “You can hardly look on the scales of any Fish,” wrote Robert Hooke in Micrographia (1665), “but you discover abundance of curiosity and beautifying."3 In the early painting Animals on Show [p. 7], a portrait of an individual rainbow trout floats freely on a ground comprised of real and imitation wood slats. Below it there is a dark square bearing an engraved echo of the same fish. The human urge to make pictures of natural creatures reflects both wonder and, in varying degrees, a desire to submit them to classification and control. So-called artistic and scientific renderings may conform to different, socially and historically determined conventions, but they arise from the same basic motivations, which Young examines in this work and in many others. Restoring the original senses of curiosity, he attends to the world, meditates on various theories of representation, respects his materials, and maintains an exploratory spirit.

|

|

Many different places have stirred Young’s imagination. He has lived in New Hampshire, upstate New York, Northern California, and Chicago. He has traveled to Italy, Germany, Greece, Pakistan, and Ecuador, among many other countries. He made a pilgrimage to the Galapagos Islands, the setting of his time-travel fantasy of accompanying Charles Darwin on the historic voyage of the Beagle. But a map of Young’s personal and artistic journey would not show an orderly progression from point A to point B, but rather a spiderweb of lines connecting territories whose edges yet remain unexplored. Thus discovery is always possible, and change of the contours inevitable.

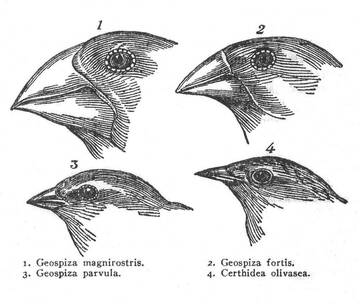

During his five years aboard the Beagle (December 1831–October 1836), Darwin made the observations (and gathered the extensive collections of specimens) that led to his famous theory of evolution by natural selection, formulated in notebooks beginning in 1837 and published as The Origin of Species in 1859. Thoroughly enthralled by the succession of different environments—Brazil, Argentina, Tierra del Fuego, Chile, the Galapagos and Pacific Islands, New Zealand, Australia, and the islands of the Indian Ocean—Darwin later wrote in his Autobiography, “I give myself great credit in not being crazy out of delight.”4 It is this quality of delight that makes Darwin’s writings so enduringly engaging; they captivate by imagery more than analysis. As a practicing scientist, Young was involved with the microbiological and genetic research that has substantiated Darwin’s intuitions. But like many, he continues to find inspiration in the nineteenth-century pioneer’s metaphorical language and intrepid imagination. |

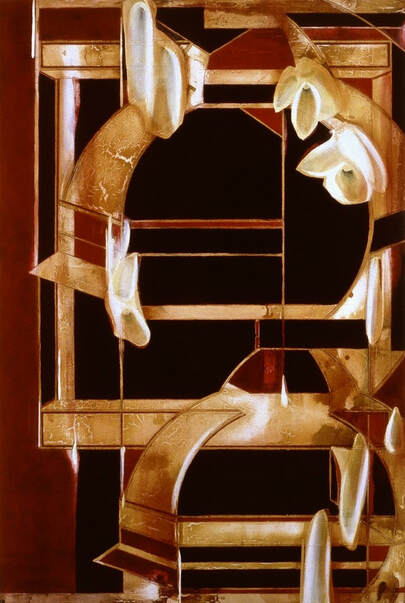

Vase and Red, 1989

Egg tempera on wood panel, 30 x 23 in. |

|

Wall in the artist’s home with Russian icons alongside

Rhymes are Games, 1996. Egg tempera on wood panel, 44 x 34 in. |

Evolution by natural selection, according to the multidisciplinary scholar Robert Maxwell Young, “is arguably the most important idea in the history of the natural and human sciences” because it is “the process which accounts for the history of living nature, including human nature.”5 This idea—humbling and inspiring, comforting and terrifying—is at the core of Andrew Young’s art, on conscious and unconscious levels. Darwin’s controversial but compelling theory posits natural selection as an active agent, affecting all living things at all times. “Let it be borne in mind,” Darwin wrote, “how infinitely complex and close-fitting are the mutual relations of all organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life."6 Young, fully aware of the environmental depredations that have occurred since Darwin’s time, honors this charge by working to restore a connection with nature as a physical and spiritual touchstone.

|

Searching Constructions

Change is the subject and substance of Young’s art. Adaptation, rupture, accident, contact, renunciation, absorption, cultivation, repetition: alteration can occur through any combination of such physical and emotional forces. In more concrete terms pertinent to artistic process, a motif might recur until its significance is fulfilled and then disappear; a medium might be set aside and found materials taken up; a stray drip of paint could take on the shape of a flower; a shift in scale might lead to a redefined realism. “Battle within battle must ever be recurring with varying success,” wrote Darwin of the struggle for existence, “and yet in the long run the forces are so nicely balanced, that the face of nature remains uniform for long periods of time."7 Surveying Young’s work over some twenty years provides evidence of such battles and also an impression of continuity.

Change is the subject and substance of Young’s art. Adaptation, rupture, accident, contact, renunciation, absorption, cultivation, repetition: alteration can occur through any combination of such physical and emotional forces. In more concrete terms pertinent to artistic process, a motif might recur until its significance is fulfilled and then disappear; a medium might be set aside and found materials taken up; a stray drip of paint could take on the shape of a flower; a shift in scale might lead to a redefined realism. “Battle within battle must ever be recurring with varying success,” wrote Darwin of the struggle for existence, “and yet in the long run the forces are so nicely balanced, that the face of nature remains uniform for long periods of time."7 Surveying Young’s work over some twenty years provides evidence of such battles and also an impression of continuity.

|

Young was in art school in the late 1980s, and he may be described (in the parlance of those years) as engaging in a “structuralist activity,” that is, not only performing a structural analysis of the figurative tradition of Western art, but also structurally engineering new objects.8 Construction is crucial to the meaning and impact of Young’s work: components and tools are deliberately chosen and thoughtfully employed, and the eventual state of finish is satisfying but never inert. The paintings retain an aspect of mutability because the artist has collaborated with his materials. Anticipating predictable outcomes and allowing for chance variations, he exerts control over paint, paper, and ink while also recognizing their inherent properties.

Young first became well known, in the early 1990s, for paintings made with tempera, which he mixed himself using egg yolk and hand-ground mineral pigments. He deployed this venerable medium, most commonly associated with the fifteenth-century Italian Renaissance masters, in a series of panel paintings that honor the past while seeking connection to the present. Young conveys this dual message through a series of formal reversals: of positive and negative space, line and color, figuration and pattern. Philosopher and linguist Ludwig Wittgenstein declared in his Tractatus that “a picture cannot depict its pictorial form: it displays it."9 By this he meant that we interpret a picture’s formal elements—line, color, texture, shape, and so on—as purposefully designed to communicate a quality, idea, or feeling. This seems true of (for example) the Renaissance frescoes and Russian icons to which Young refers in his tempera panels. But the Modernist innovation, to which he is also an heir, was to posit a work of art that is not necessarily a picture, thus making possible the display of depiction that Wittgenstein denies. |

Two Lights Placed There, 1994

Egg tempera on wood panel, 47 x 32 in. |

|

Light Pretending, 1994

Egg tempera on wood panel, 24.5 x 17.5 in. |

While setting up certain depictive expectations with color, material, and format, Young also forces the viewer to attend to display. The 1989 panel Vase and Red [p.8], for example, appears to be a straightforward, elegant still-life: a white vase, perhaps patterned with blue, stands on a table or shelf, against a red background. However, the work’s construction points toward something more complex and expansive. Over a sturdy cherry-wood panel, Young applied a ground of gesso (rabbitskin glue, gilder’s whiting, and zinc oxide) and polished it to a sheen. Then he stenciled a grid of tiny Greek crosses, of the sort one might find embossed or engraved on a shield, and painted in the forms. Next, still pursuing the so-called background as his primary subject, the artist poured and brushed layers of dilute emulsion—pigmented with Venetian red, alizarin crimson, and rose madder—over the panel’s surface, allowing the paint to pool around the cross shapes. Only now did he incise the horizontal line that hints at a third dimension. By basing his composition on a vacant repository (here, a shelf; elsewhere, a niche, frame, or aperture of some kind), Young ensures the evacuation of conventional portraiture or narrative. Then, as he describes it, he “populated” the setting with a liminal figure or figural stand-in. Gouged out of the rich scarlet curtain and hovering on the threshold of conscious perception, the pale shape suggests a container for more complicated feelings and ideas.

|

As a result of (and, ultimately, in conjunction with) the formal reversals described above, illumination attains a purely expressive rather than primarily descriptive function in Young’s tempera paintings. The evocatively titled works Two Lights Placed There and Light Pretending, both of 1994, directly address this transformation. The larger of the two panels, Two Lights Placed There, presents a marquetry-like design of ebony and amber tonalities, overlaid with strokes and streaks of ivory. In certain areas, the white medium coalesces into petals, brightening and virtually scenting the geometric architecture over which they hover and settle. Elusive yet palpable, these invented blossoms are radiant, gestural improvisations representing the principle of generation. One is irresistibly reminded that tempera is comprised of the yolks of eggs, symbolic of life and resurrection.

|

In other passages, along the painted and incised joins between fields of color, the paint asserts its own liquid identity, willfully trickling. But because Young works with his panels laid out horizontally, on the floor, there is a subtle game here: he draws the drips with a precise hand. Imitating the force of gravity, he points to the artificiality of pictorial representation and asserts the flatness of the panel’s surface. Another way in which the viewer is made aware of the paint’s materiality and potential independence from descriptive duty is through craquelure, the network of small fissures resulting from uneven drying time or climate changes. These cracks connote aging or organic decay but denote only themselves. Having observed this phenomenon in old paintings and in test panels in his studio, Young learned to instigate and control it, placing a pigment-rich mixture over an oil-laden one and then encouraging the cracking with a blade or needle.

|

Untitled (wc-118), 1994/97

Watercolor and gouache on museum board, 20 x 16 in. |

|

Untitled (wc-119), 1994/97

Watercolor and gouache on museum board, 20 x 16 in. |

Flaws, then, can be indicators of human presence. This mark-making impulse emerges in the representational traditions of many cultures, even those that proscribe graven images. When Young lived in Lahore, Pakistan, on a fellowship in 1993, he noticed that weavers would introduce small imperfections within the orderly geometric designs that symbolize the cosmology of Islamic belief. Collecting small artifacts, gathering substances for pigments, traveling around the country, talking with his Pakistani hosts and students, Young began to sense a universal significance in the crystalline patterns and stylized arabesques seen in Mughal tile work, textiles, illuminated manuscripts, and architecture. In a series of small watercolors [p. 11], he translated this rich visual language into his own terms: symmetrical, repeatable patterns sit neatly within boundaries, but tinted washes escape these parameters, seeping toward the margins and eluding configuration.

|

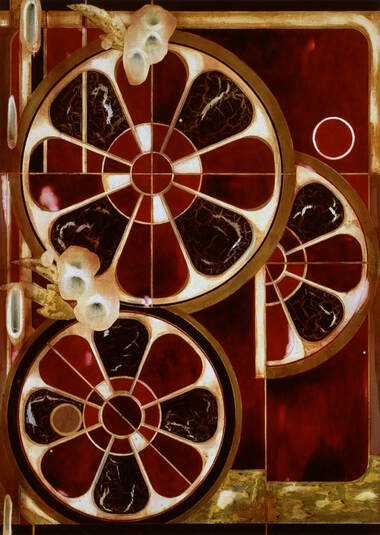

As Young recalls, about two years passed before paintings that explicitly reference his Pakistani experience “started to emerge,” motivated by internal impulse rather than external influence.10 In works made between 1995 and 1997, he tautened the relationship between structure and symbol, the interlocked means through which human beings lend order and meaning to their untidy lives and restless spirits. The polished, sectioned circles in the 1995 panel Music in Phrases [p. 12] seem significant but initially resist interpretation: they could be stylized rosettes, cross-sections of citrus fruits, fossilized diatoms, pie charts, targets, or clockwork cogs. However, their varied size, chromatic regularity, and indeterminate setting serve to undermine some of these hypotheses, as does the comparative naturalism of the superimposed white flowers.

|

The title provides a clue to a different meaning, in conjunction with the compositional framework, which suggests the lines of a musical staff. In this context, the circles’ radiant energy is both auditory, connoting pitch and reverberation, and visual, implying a dynamic sequence of notes. In this painting as in a musical performance—and as in life—expression and adaptation occur within a coded structure. Through formal innovation, manual intervention, and cross-cultural allusion, Young moves in his tempera panels from respectful historicism into far more mysterious territory, where change is inevitable and constant. Often but not only beautiful, these works are wholly contemporary in their searching melancholy.

Caught by Hand Sketching out his theory of evolution by natural selection in 1842, Darwin made the following observation: “We must look at every complicated mechanism and instinct, as the summary of a long history of useful contrivances, much like a work of art.”11 Young’s tempera paintings, made over the course of some thirteen years, reflect incremental change and purposeful innovation. An artist devoted to discovery, Young keeps himself carefully attuned to the balance between expression and execution. As critics and audiences responded to these richly enigmatic pieces, he tested and extended the capacities of tempera while continually questioning its allure. |

Music in Phrases, 1995

Egg tempera on wood panel, 44 x 32 in. |

In around 1997, Young’s artistic practice underwent a significant shift. Feeling as if he were “taking what he could carry” from one environment to another, he realized that to communicate his response to, and eventual acceptance of, his altered circumstances, he would need to reach for different materials and compositional modes.12 Instinctively, he began to make drawings on small pieces of paper, which he would grasp and fold as if seeking tactile, externalized reconciliation with an intensely introspective process. Although he had no specific purpose in mind for these personal notations—indeed, they would remain stashed in the pockets of his work clothes for an indefinite period—they ultimately led to a new body of work that continues to evolve today.13

|

All Senses series (c-01), 1998

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 9 x 7.5 in. |

In several of these drawings, bird silhouettes signal the artist’s presence, but also his dislocation. Arranging the avian figures in increasingly complex collages, Young found that the taxonomic exercise was facilitating a renewed connection to the natural world. While he acknowledges certain conventions in his designations for these untitled works—they are assigned uninflected numeric codes modified by descriptive phrases, as individuals are recorded within species—Young’s process infuses prototypes such as field guides, herbaria, and other manuals with new expressive potential. Nearly all the elements in his collages are hand-made; he stains smooth cotton drawing papers with solutions of pigment, water, gum arabic, and glycerin, and paints on Chinese rice paper with watercolor and gouache, also made with hand-ground pigment. The occasional appearance of other materials like stamps or postcards—collected, like the substances used for pigments, rather than found—tends to heighten the crafted nature of the whole, as critic Tom Breidenbach noted in 2002.14 Assembling these individual pieces into larger compositions, Young structurally reiterates the initial unfolding of those transitional notations.

|

|

Although the materials differ, many elements link these collage-based works with their tempera predecessors. Young remains concerned with the oscillation between foreground and background, positive and negative space, color and line, abstraction and figuration. His devotion to construction, and his concomitant responsiveness to accident, are still manifest in visible seams, edges, strokes, and drips. Just as he employed tempera by alluding to and departing from past traditions, Young practices collage in a likewise original manner.

|

All Senses series (c-02), 1998

Collages of hand-painted papers on museum board, 7 x 5.5 in. |

|

All Senses series (c-03), 1998

Collages of hand-painted papers on museum board, 6.5 x 7 in. |

These collage paintings are more than personal scrapbook pages or updated field guides to birds, plants, and insects. In a number of different ways, Young’s works call attention to the nature of representation and the representation of nature. Some do so with reference to systems of classification; others through recollection of other pictorial modes; still others by exploring archetypal forms and essences. In many examples, all these strategies are operative. Young, whose activity was described above as structuralist, is deeply concerned with the activity of signs, that is, things taken to stand for something else. As defined by philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce around the turn of the twentieth century, signs fall into three basic categories with respect to referents, or objects in the real world: icons, which resemble referents (an anatomical drawing, stylized floral wallpaper); symbols, which are linked to referents by arbitrary but agreed-upon conventions (language, money); and indexes, which are causally related to referents (fingerprints, cast shadows, the stain left on a page by a pressed flower). These are rich conceptual categories precisely because images and ideas so often blur the boundaries between them. For example, a photograph is both icon and index; an illuminated manuscript both symbol and icon; a word written in the sand both index and symbol.

|

As Modernist artists first discovered in the early decades of the twentieth century—concurrently with the publication of Peirce’s semiotic theories—collage creates new kinds of meaning by mobilizing all three types of sign. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque used pieces of faux-wood-grained papers to rupture iconicity, exposing the pretense of resemblant representation. The Futurists cut up newspapers and reassembled the broken typography into jarringly nonsensical concrete poetry, dismantling and thereby reappropriating a symbolic code. And Jean Arp and other Dadaists created purely indexical art by scattering pieces of paper randomly on a surface, where they indicate nothing other than what they are.15

|

Young, well acquainted with these and many other art-historical, cultural, and scientific precedents, has made the medium his own. Although many of the papers in his collages have the worn appearance of scraps long discarded, he actually produces this effect himself, as noted above: painting, staining, sanding, creasing, and tearing them to create tones and edges of varying transparency and precision. The result is profoundly authentic, as opposed to counterfeit, because the direct traces of the artist’s hand and the essential qualities of the materials are preserved. Following from this, Young’s arrangement of the elements is similarly deliberate, intimate, and meaningful. The display of depiction, initiated in the tempera panels as a commentary on representational convention, now becomes a means of personal communication and revelation.

Young ranges from pared-down minimalism to layered proliferation in his collage paintings. C-80, a deceptively simple arrangement of multicolored rectangles and squares over larger, neutrally toned rectangles, is an early, investigative piece in which the artist deliberately restricted himself to essential elements. Having worked with the forms and conceptual implications of vessels in his tempera paintings, he now set himself the challenge of portraying feelings or supplying associations without delineating a container for them. Idealism and materialism here dovetail in an attitude of tranquil but alert poise. The larger work c-102 also seems to perform a purely geometric and chromatic exercise, in the manner of a test strip, perhaps, or a weaving. However, examination of the blue bands reveals different proportions of cobalt and navy, which creates a slight imbalance of the upper and lower blocks and hints at organic transformation at a cellular level. |

Place and Formula series (c-102), 1999/2003

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board. 31 x 23.5 in. |

|

Place and Formula series (c-80), 1999

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 15 x 12 in. |

The careful abutting of rectilinear edges in c-80 and c-102 points to a certain discipline that is essential in all of Young’s work, even (or especially) when curving and organic elements appear as well. Displaying the potency of adjacency, these edges also reinforce the flatness and thinness of the paper components, qualities undiminished by the painting’s eventual transition from the horizontal work surface (floor) to the vertical display surface (wall). The internal spaces created by Young respect but do not restrict themselves to these two dimensions. Through mirroring, folding, and rotation, he establishes a third dimension of depth; through memory, anticipation, and catalysis, he embraces the fourth dimension of time.

|

|

Instinctively drawn to collage’s basic indexical capacity to retain the imprint of his touch, Young realized he could also introduce iconic (resembling) and symbolic (conventional) signs. Plant and bird shapes thus find their way into the imagery, very much in the manner of the gradual population of an environment by diverse species. Generation and replication, a theme treated in Two Lights Placed There, is addressed anew in c-251. In this floral meditation, Young acknowledges the decorative appeal of the botanical renderings found in field guides, but at the same time questions their capacity to convey the variety and mystery of life. The artist based these images not on observation but on memory, both mental and physical, and on the behavior of his materials. The forms are embedded in his imagination just as the watercolor has soaked into the paper support.

|

Caught by Hand series (c-251), 2002

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 27.5 x 21.25 in. |

|

Variations in the beaks of finches originally published in

Charles Darwin, The Zoology of the Voyage of the HMS Beagle, pt. 2, Birds (London, John Gould, 1841). |

The grid of four plants in c-251 points to Young’s interest in morphology—the study of the form and structure of organisms—and in the etymologically related notions of morphosis (developmental variation brought about by changes in the external environment), amorphism (lack of shape, structure, or classifying features), and metamorphosis (complete or marked change). The collage medium, with its particular characteristics and conditions, prompted an alteration in the floral elements that initially flourished in tempera panels. The bird forms, too, have proven adaptable. At their most prolific, they seem to lack individual traits, but Young checks the impetus toward reductive archetype by introducing a genetic shift: in c-310, the upper birds are black, but the lower ones exhibit signs of a gradual mutation toward a deep plum hue.

|

|

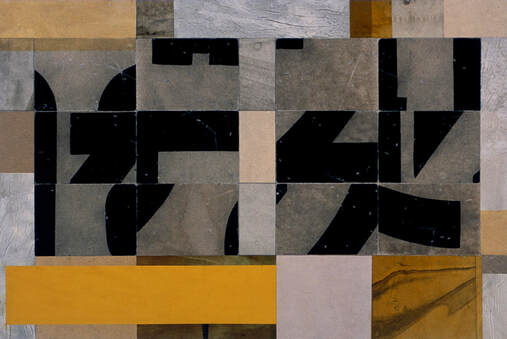

As silhouettes, the birds become emblems, first alone and then in combination with other symbolic or totemic forms. They predominate in several works from around 2000.16 But in c-310, segmented circles, similar to those seen in Music and Phrases, begin to eclipse the birds; we seem to witness one of the “battles within battles” being fought in the struggle for existence. Textual elements may be seen as another new signifying species in the collages, seemingly cultivated from the paper on which they are typically printed or inscribed. Morphology, as a scholarly discipline, pertains not only to organic forms but also to “the structure of words in a language, including patterns of inflections and derivations,” and Young brings all his deft acuity to bear on this theme. Painting the shapes of letters and numerals, applying labels, letterpress, and stamps, and transcribing phrases from poems and prose, Young portrays the multivalence and, perhaps, the inexorability of our communicative impulses. In rather imposing pieces such as c-233, the fragmentary characters seem, according to critic John Brunetti, “deliberately cropped and scrambled by the boundaries of rectangular, creased edges, as if to obscure their identification during the act of public revelation."17 Young elaborates as follows: “All of our descriptions, formulas, and equations, in the form of genetic codes, identity codes, and other numerical notations, are set up to describe the essence of matter. In [these pieces] I cut up such classifications and rearrange them, but the sense of codification is still there."18

|

Leaves and Lanterns series (c-310), 2005

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 17 x 13.5 in. |

|

Caught by Hand series (c-233), 2002

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 23.5 x 35 in. |

Young carefully and continually explores the ways in which human dexterity (manual and perceptual) can incite shifts and variations in systems we believe to be fixed or stable. The paired works c-305 and c-303 provide a glimpse into his personal mode of empiricism. For the first of the two, c-305, Young began by applying a ground of deep, matte, nearly black gouache to a number of small cards, each slightly larger than 4 x 5 inches in size. Then, he mixed a dilute gouache of water, titanium white, and gum arabic, using it to brush floral images onto the cards. Owing to the translucency of the medium, this is not so much a superimposition of light over dark as an extraction of light from dark, in the manner of a mezzotint, or a bleaching of light into dark, in the manner of a cyanotype (literally, a blueprint).

|

|

Certainly the leaves’ blue color references this early method of “drawing with light,” almost convincing us that the plants imprinted themselves by contact, through the agency of the sun. In fact the artist alone revealed the latent images. Rubbing the virtually invisible painted traces with his fingers, he rendered the gum arabic tacky enough to hold a combination of finely ground cerulean blue, indigo, and aquamarine pigments. Like a cyanotype, each of these images is unique. But following the early pioneer of photography William Henry Fox Talbot—naturalist, linguist, antiquarian, and contemporary of Darwin—Young is also concerned with the possibility that one matrix might generate multiple images.19

|

Leaves and Lanterns series, (c-305), 2005

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 15.25 x 11.75 in. |

|

Leaves and Lanterns series, (c-303), 2005

Collage of hand-painted papers on museum board, 15 x 11.75 in. |

The painting c-303 resulted from his decision to replicate c-305 on a different basis. Instead of creating individual components for assembly in a larger whole, this time Young determined the final scale of the work at the outset, preparing a single sheet of paper and drawing a grid of nine rectangles with a red-tinted medium. Then he set about echoing c-305’s floral forms with watercolors and gouaches of various colors, not so much tracing or transferring the shapes but recovering them through gesture. The loss of density that occurs from the first work to the second is an eloquent commentary on the transience of sensory experience and the persistence of memory.

|

|

Scale in Young’s work has often been a function of his materials and always a result of his physical engagement with them. The intimate appeal of his collages has to do with their hand-held size and page-like proportions, just as the architectural presence of the temperas has to do with their corporeal dimensions and niche-like compositions. In 2004, Young encountered a new material—discarded, weather-damaged steel flashing—that inspired him to combine these effects. He cut and flattened the metal into sheets, which he then affixed to wood panels. This scarred surface, with its corrosion, dents, scratches, and nail heads, became the expressive and surprisingly fertile ground for strokes of paint, an array of painted papers, and even, in Unheard-of Riches (m-106) [p. 45], a ferrotype, a direct photographic positive on a thin piece of blackened iron.

|

Unheard-of Riches (m-106), 2004

Paint, painted papers, and found ferrotype on steel-faced wood panel, 30 x 23 in. |

|

Installation view of Promised Treasure, 2005

Paint and hand-painted papers on four wood panels, 4 x 13 ft. each. Budlong Woods Branch Library, City of Chicago Public Arts Commission. |

At around the same time he was scaling down a large, unwieldy coil of sheet metal in his small studio, Young embarked on a project that required him to scale up his intimate motifs for a large public space. On the basis of watercolor sketches, he earned a commission to decorate the reading room of the Budlong Woods Public Library in northwest Chicago, which resulted in four murals collectively titled Promised Treasure [p. 18]. His design scheme included the fronds, stalks, birds, and text passages also seen in collages such as c-208 [p. 19], and he wanted to retain their grace and tranquility while increasing their size sixteen-fold and adjusting their contours to compensate for the distortion caused by viewing from below. This involved a much more complicated transposition than that seen in the comparison between c-305 and c-303, but Young took the same basic approach of “seeing with his eyes closed,” as he puts it.20 |

Greater and Lesser Lights series (c-208), 2001/2002

Collage of hand-painted papers, with Chinese text and stamp, on museum board, 25 x 39.25 in.

Collage of hand-painted papers, with Chinese text and stamp, on museum board, 25 x 39.25 in.

A recurring reddish frond, about fourteen inches tall in c-208, measures four feet in one of the murals. Leaning over the sheet of rice paper with a loaded brush, Young practiced a technique related to that used by Asian sumi-ink painters, fanning a large brush against the surface and letting changes of pressure transfer the gouache to the page. Repeating at arm’s length the movements already familiar to his fingers, he could sense the integrity of his gestures but could not watch the motif emerging. Nor did he see the compositions until the point of their installation in the library in spring 2005, for he started with individual elements, such as the frond on rice paper, and then applied them to a total of twelve square panels, which were finally affixed to four thirteen-foot-long rectangular supports. With very little room for error, Young effected the adaptations necessary for his imagery to survive in a very different environment while preserving its essential characteristics.

|

Felt But Not Known

Young’s art emerges from all the introspective impulses (memory, desire, loss, love), physical gestures (turning, reaching, flattening, sorting), and sensory faculties (sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell) through which he knows the world. If we follow him in believing that these are universal aspects of the human condition, we can find in his art a vision of corporeal and conceptual integration with nature. Documents of his moments of discovery, Young’s works may in turn prompt a discovery, or recovery, on the part of a viewer. Science and art both depend upon experimentation, but the status of these disciplines and their end-products is historically and culturally determined. Today, certain social, moral, political, religious, economic, and literary discourses contribute to a tendency to oppose science and art. This polarization compromises both pursuits. The artist and the scientist share a concern with the as-yet-invisible and unproven; both charge themselves with rendering the new kinds of experience they encounter. And both ultimately emulate the processes already and always at work in nature. |

Leaves and Lanterns series (c-320), 2005

Collage of hand-painted papers, with found text, on museum board, 21.5 x 16.25 in. |

|

Man by selection can certainly produce great results, and can adapt organic beings to his own uses, through the accumulation of slight but useful variations, given to him by the hand of Nature. But Natural Selection…is a power incessantly ready for action, and is as immeasurably superior to man’s feeble efforts, as the works of Nature are to those of Art.21

|

|

Untitled, 1992. Watercolor and gouache

on museumboard, 18 x 14 in. Collection of Helen and William McCrae |

|

|

1 The author thanks Joyce Morehouse of Washington Island for her transcription of this passage.

2 “Only Collect: Our Secret Agent Goes Digging for Five Artists’ Hidden Treasures,” Mouth to Mouth (Chicago) 2, no. 3 (spring/summer 2004), p. 42. 3 OED Online, s.v. “curiosity, n.,” http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50056021 (accessed September 19, 2005). 4 Cited in Mark Ridley, ed., The Essential Darwin (London: Unwin Hyman, 1987), p. 6. See Charles Darwin, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809–1882, ed. Nora Barlow (London: Collins, 1958); and The Beagle Record: Selections from the Original Pictorial Records and Written Accounts of the Voyage of HMS Beagle, ed. Richard Keynes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979). 5 Robert Maxwell Young (no relation to the artist), “Science and the Humanities in the Understanding of Human Nature,” lecture presented on May 25, 2000, On Line Opinion, http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/print.asp?article=1171 (accessed September 22, 2005). See also Young’s pioneering early essays, collected in Darwin’s Metaphor: Nature’s Place in Victorian Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). 6 Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 67. 7 Darwin, Origin of Species, p. 61. 8 This definition was formulated by Roland Barthes; see Yve-Alain Bois, “Formalism and Structuralism,” in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Art since 1900 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004), pp. 32–39. 9 Cited in W. J. T. Mitchell, Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), p. 39. 10 “Portrait of an Artist: an Interview with Andrew Young,” Entre Nous (Chicago) 1, no. 3 (July–September 1997), p. 6. 11 Cited in R. Young, Darwin’s Metaphor, p. 88. 12 Telephone conversation with the artist, October 5, 2005. 13 See Andrew Young: Collages (Urbana-Champaign: I Space, University of Illinois, 2001). 14 Tom Breidenbach, “Andrew Young at Littlejohn Contemporary,” Artforum XX, no. XX (April 2002), p. 141. 15 For analyses and reproductions, see Foster et al., Art since 1900, pp. 95–96, 112–17, and 157–58. 16 See, for example, Untitled (c-100), Migrations series, 1999, in Birdspace: A Post-Audubon Artists’ Aviary (New Orleans: Contemporary Arts Center, 2004), ill. p. 33. 17 John Brunetti, “Unfolding the Essence of Being: The Collages of Andrew Young,” in Andrew Young: Collages, p. 9. 18 Cited in Julie Sasse, “Transcendent Nature: Sources of Inquiry in the Art of Andrew Young,” in Andrew Young: Collages, p. 22. 19 On cyanotype and Talbot’s other technical innovations, calotype and photoglyphic engraving, see Sun Pictures: Talbot and Photogravure, text and entries by Larry J. Schaaf (New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., 2003). 20 Telephone conversation with the artist, October 5, 2005. 21 Darwin, Origin of Species, p. 53. |

Full-color, printed exhibition catalogs are available with the above essay. Please contact the artist to inquire.