Selected Catalog Essays

Out of Eden (September 6 - November 30, 1997)

The Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Kansas City 1997

- Dana Self, Curator

From the exhibition press release:

We are stardust, we are golden, and we've got to get ourselves back to the garden. - Joni Mitchell

Because we are exiles from nature, forgetting or forgoing the pleasures of a physical relationship with the land and the seasons, nature is our obsession. From California's Yosemite National Park to New York City's Central Park, we have claimed nature as our privilege to enjoy. To reconcile with nature we often plant flower, herb, or vegetable gardens, creating an Arcadian site on which to nurture living organisms. The earth and its plants' shifting stages allow us to feel part of a continuum, part of something larger than ourselves, our jobs, our families, and our daily lives. We cast ourselves into nature's thicket - a site of fantasy and idealism - which is, according to historian Simon Schama, "the heart of one of our most powerful yearnings: the craving to find in nature a consolation for our mortality."

|

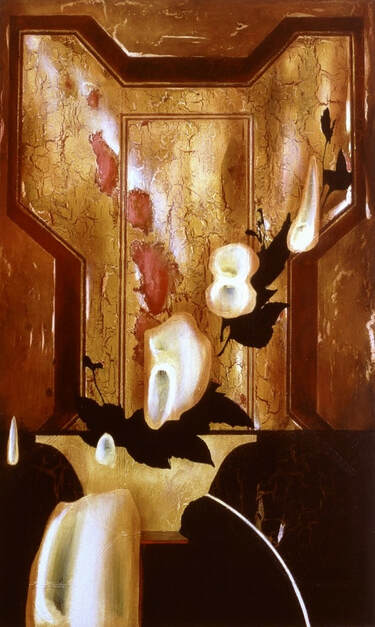

Out of Eden (catalog excerpt) Andrew Young and Darren Waterston also work on the borderline of the abstract and the real, imagination and reality. In Andrew Young’s painting, still life and abstraction morph from one to the other, and fluid interchange between them denotes the ambiguous relationship between nature and abstraction. Young “wants to make the objects in his paintings ‘vanish or become an apparition, in such a way that recognition is really the issue of the work. I wanted to get that simultaneously familiar and yet kind of exhaustive or elusive kind of experience.’”11 The works create an airless and timeless sight, heightened by the artist’s material choices. Using egg tempera on wood panel, Young reinterprets the shimmering work of Sienese painter Simone Martini. The past becomes, then, actively present in these works, suggesting to us that time is collapsible, and ultimately proposing a new temporal space. In the painting Into a Place we enter the title’s “place” through the flowers which recede from the front of the picture plane through the ambiguous middle space to the rear. With each successive metamorphosing flower, the painting becomes denser and meaning seems more intricate. The viewer may waffle between the architectural framed image in the work and the flowers themselves, which suggest that they were at one time part of a still life but have since transformed into this new configuration. Young has liberated the still life. Images float freely, suggesting that boundaries between natural and artificial, abstract and real are merely constructs. Young questions any division between past and present, real and imaginary, and through his paintings we may enter this new temporal and ethereal space. |

Andrew Young, Into a Place, 1994

Egg tempera on wood panel, 44 x 27 in. |

Colonizing the borderland between abstract and real, Darren Waterston discloses cycles of a constantly breeding and renewing nature. Waterston’s paintings appear to have prized open a semi-natural realm lodged between botanical specimens and bazaar unknown places. Like Young, he often paints on wood panels, making the work seem of a different time. However, unlike Young’s paintings which are more abstract and suffused with an otherworldly golden light, some of Waterston’s scenes are darkly ominous. His seem to be specimens on the verge of decaying and dying. Contrary to Young’s paintings which appear to be growing, the abstract passages in Waterston’s paintings are dissolving. In Passage, the surface of the painting is awash with streaming paint which creates tension between the artificial surface of the painting and the atmospheric interior of the image.

|

Darren Waterston, Eamon’s Thought, 1995

Oil paint on wood panel, 39 x 60 in. |

The illusory affect of Passage’s surface is that of a glass slide covering a slightly sinister world teeming with micro-organisms. Whereas Young seems to render the invisible, visible, Waterston makes the subvisible visible. While Young’s paintings conjure an ethereal, inviting space, Waterston’s have the opposite effect. They seduce the viewer to look closely, yet the abstraction is a barrier shielding the slightly decaying and slightly vandalized plants. Waterston states, “I’m interested in the sensual as well as the perverse…in things that are repelling in the same moment they are drawing you in. …I want the paintings to say, ‘Don’t go here. The fantasy is out of reach.’”12 But often the unattainable fantasy is the most desirable one. Waterston recognizes the allure of a landscape painting suffused with meaning that appears to be lurking just beneath the surface.

- Dana Self, curator The Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art and Design Kansas City, MO |

|

11 David McCracken, "Young's Paintings Look Backward, Forward," Chicago Tribune, October 12, 1990, n.p.

12 Michael Scott, “Inspiration Is Where You Find It—For Darren Waterston, That’s Denman Island," The Vancouver Sun, September 3, 1995, n.p. |

© The above artworks may be protected by copyright. They are posted on this site in accordance with

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.

fair use principles, and are only being used for informational and educational purposes.